An entrepreneur has finalized a comprehensive business plan for a new manufacturing facility in Papua New Guinea. The market analysis is sound, financial projections robust, and the technology proven. Yet, months later, the project is stalled—not by market forces or funding, but by a complex and often underestimated administrative landscape.

This scenario is a common challenge for investors entering new jurisdictions, where the path to operational readiness is lined with regulatory hurdles demanding careful navigation.

Successfully launching a manufacturing plant in Papua New Guinea (PNG) depends on a clear understanding of its unique legal and environmental framework. While the nation offers significant opportunities, particularly in sustainable industries, its regulatory processes are unique and require a diligent approach. This guide provides a structured overview of the essential steps—from securing environmental clearance to obtaining an operating license—to ensure a project moves from blueprint to reality without costly delays.

Understanding the Regulatory Landscape in PNG

Before any physical construction or operation can begin, an investor must work with two primary government bodies. Misunderstanding their distinct roles is a frequent source of project delays.

-

Conservation and Environment Protection Authority (CEPA): As the custodian of PNG’s environmental laws, CEPA is responsible for assessing and managing the potential environmental impact of any new development. Its approval is a non-negotiable prerequisite for any project that alters the environment.

-

Investment Promotion Authority (IPA): The IPA serves as the central point for registering and certifying foreign investment. It ensures that new enterprises comply with national business laws and contribute positively to the economy.

Based on experience from J.v.G. turnkey projects, successful execution depends on addressing these two areas sequentially and with meticulous preparation. The CEPA permit must be secured before pursuing the full range of operational licenses from the IPA and other bodies.

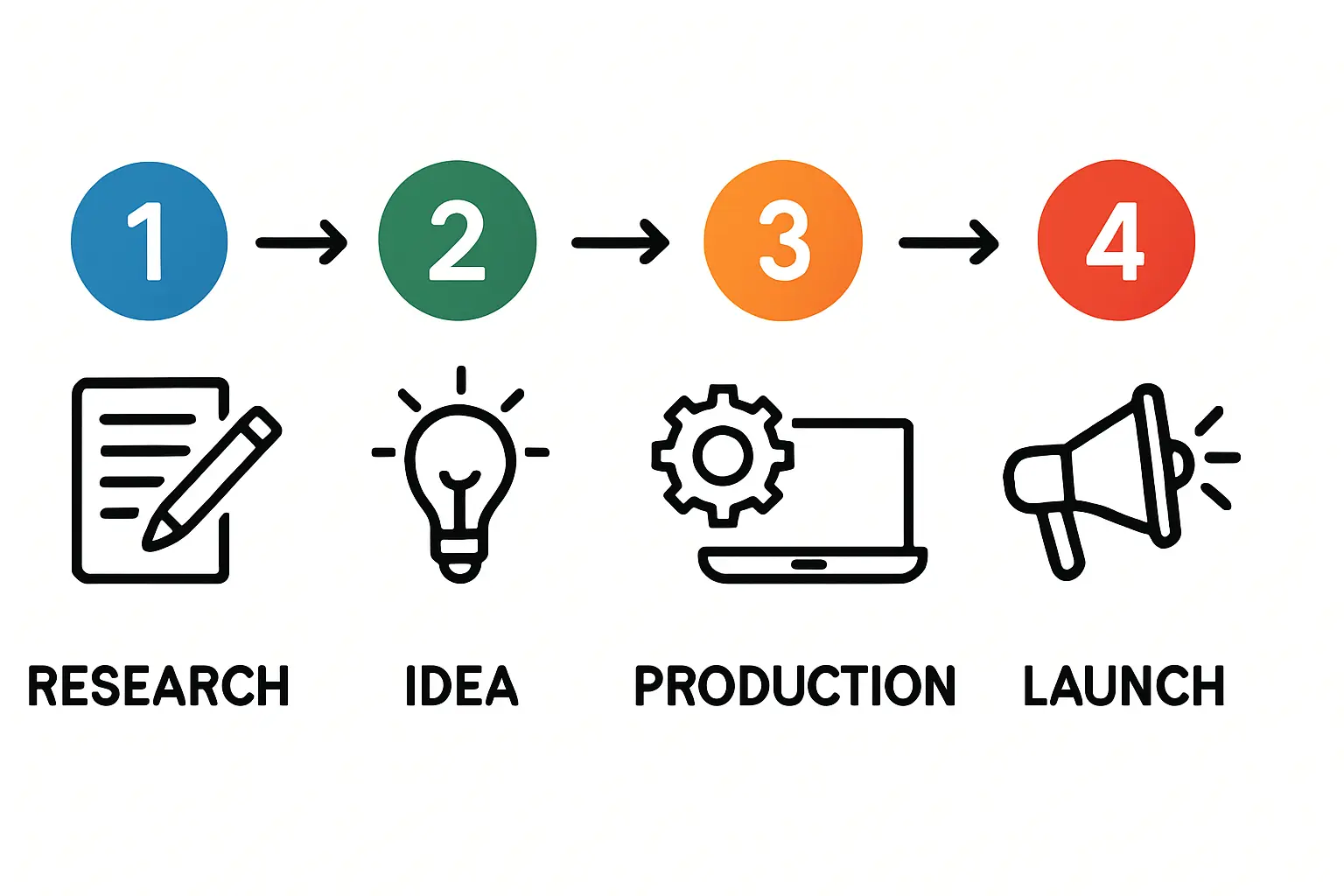

Step 1: The Environmental Permit with CEPA

The cornerstone of the regulatory process in PNG is the Environmental Permit, granted under the Environment Act 2000. This is the most critical and often the most time-consuming step. Attempting to bypass or rush this stage can lead to significant legal and financial penalties, including the complete halt of a project.

The Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA)

Central to the CEPA application is the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA). This is not a mere formality but a detailed technical study of the project’s potential effects on the local ecosystem and communities. A comprehensive EIA typically includes:

- Baseline Studies: In-depth analysis of the existing environment, including water quality, air quality, biodiversity, and socio-economic conditions.

- Impact Prediction: A scientific forecast of the potential positive and negative impacts of the factory’s construction and operation.

- Mitigation Measures: A clear plan outlining the strategies and technologies that will be used to minimize negative environmental impacts.

- Environmental Management Plan (EMP): A framework for ongoing monitoring and management to ensure compliance throughout the project’s lifecycle.

The quality and thoroughness of the EIA directly influence the outcome and timeline of the permit application. For investors new to the region, partnering with a reputable in-country environmental consultant is essential for producing a report that meets CEPA’s stringent standards.

The Application Process Explained

The journey to securing an Environmental Permit follows a structured, multi-stage process:

-

Screening: The project is classified based on its potential environmental impact (Level 1, 2, or 3). Most manufacturing facilities fall into Level 2 or 3, requiring a full EIA.

-

Scoping: CEPA, in consultation with the project proponent, defines the specific terms of reference for the EIA study.

-

EIA Submission: The completed EIA report is submitted to CEPA for technical review.

-

Public Consultation: For significant projects, the EIA is made available for public and stakeholder review and comment. This step is crucial for building local support and addressing community concerns.

-

Final Decision: CEPA reviews the EIA, technical feedback, and public comments before making a final decision to grant or refuse the permit. Permits are typically issued with specific conditions that must be met.

A realistic timeline for this entire process can range from 6 to 18 months, depending on the project’s complexity and the quality of the submitted documentation. Preparing a detailed overview of factory building requirements in parallel will help inform the EIA.

Step 2: Securing Your Investment and Operating License with IPA

Once environmental clearance is in sight, the focus shifts to formalizing the business entity. The Investment Promotion Authority (IPA) is the gateway for foreign investors to operate legally in PNG.

The IPA Certification Process

Obtaining an IPA Certificate is mandatory for any foreign enterprise. The application requires you to demonstrate that the investment is commercially viable and aligns with the national interest. Key submission documents include:

- A well-structured business plan for your manufacturing plant, complete with detailed financial projections.

- Proof of financial capacity to fund the proposed investment.

- Details of the company’s shareholding structure and directors.

- A summary of the project’s expected economic benefits, such as job creation and technology transfer.

The IPA process is generally more straightforward than the CEPA process, with processing times typically measured in weeks rather than months, provided all documentation is in order.

Integrating with Other Necessary Permits

IPA certification is a crucial milestone, but it is not the final step. It allows the company to apply for other essential permits, which may include:

- Building and Planning Permits from local or provincial authorities.

- Sector-specific licenses (e.g., for water use or waste disposal).

- Work permits and visas for expatriate staff.

A comprehensive understanding of the total investment requirements for a solar factory must also account for the costs and time associated with obtaining all these secondary permits.

Best Practices for Navigating the Process

Success in PNG’s regulatory environment is less about speed and more about strategy and preparation.

Engage Local Expertise Early

Engaging experienced, on-the-ground consultants is invaluable. They understand the administrative culture, have established relationships with government agencies, and can anticipate and resolve potential issues before they cause delays.

Meticulous Documentation

Incomplete or inaccurate applications are the single most common reason for delays. Every document submitted to CEPA and the IPA must be precise, comprehensive, and professionally prepared. Resources like the pvknowhow.com e-course provide structured guidance on assembling the foundational data needed for these applications.

Proactive Stakeholder Engagement

Building positive relationships with local government bodies, landowners, and community leaders is fundamental. Proactive communication and transparent engagement can foster goodwill and create a smoother path for project approval, particularly during the public consultation phase of the EIA.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What is the typical timeframe for securing all necessary permits in PNG?

For a medium-sized manufacturing plant, an investor should budget 12 to 24 months from starting the EIA process to achieving full operational licensing. The CEPA permit is the most time-critical element.

Are there significant fees associated with the CEPA and IPA applications?

Yes, both authorities charge application and processing fees. The fees for the CEPA process are substantially higher and depend on the project’s scale. These costs, along with fees for environmental consultants, should be factored into the initial project budget.

Is it mandatory to have a local partner or director in PNG?

While not always legally mandatory for all sectors, having a local partner or director can be highly beneficial for navigating business and community relations. The IPA can provide guidance on specific requirements for certain reserved business activities.

What are the consequences of starting construction without an environmental permit?

Commencing work without a CEPA permit is a serious offense under the Environment Act 2000. It can result in ‘stop work’ orders, substantial fines, and even prosecution of company directors—all of which cause irreparable reputational damage.

Your Path Forward

Navigating the regulatory landscape of Papua New Guinea requires a methodical, patient, and well-informed approach. The process is not a barrier but a structured pathway designed to ensure that new investments are sustainable, environmentally responsible, and beneficial for the country.

By understanding the distinct roles of CEPA and the IPA, investing in a high-quality Environmental Impact Assessment, and preparing meticulous documentation, entrepreneurs can move their projects forward with confidence. Proper planning is the key to transforming a promising business concept into a successful, compliant operational facility.