Entrepreneurs considering a new solar module factory in Brunei are often drawn to its strategic location, political stability, and clear government vision for economic diversification.

However, exploring project financing here reveals a system operating on principles distinct from conventional banking. Rooted in Islamic law, this system is not a barrier but a structured pathway that demands a fresh perspective on risk, assets, and partnership.

Brunei’s financial sector is predominantly Sharia-compliant—a framework built on ethical, asset-backed transactions. For investors accustomed to interest-based loans, this can initially seem complex. Yet, the system offers robust and viable models for funding large-scale industrial projects, including a modern solar panel factory. Understanding its core tenets is the first step toward securing capital in this promising market.

Table of Contents

Understanding the Landscape: Why Islamic Finance Dominates in Brunei

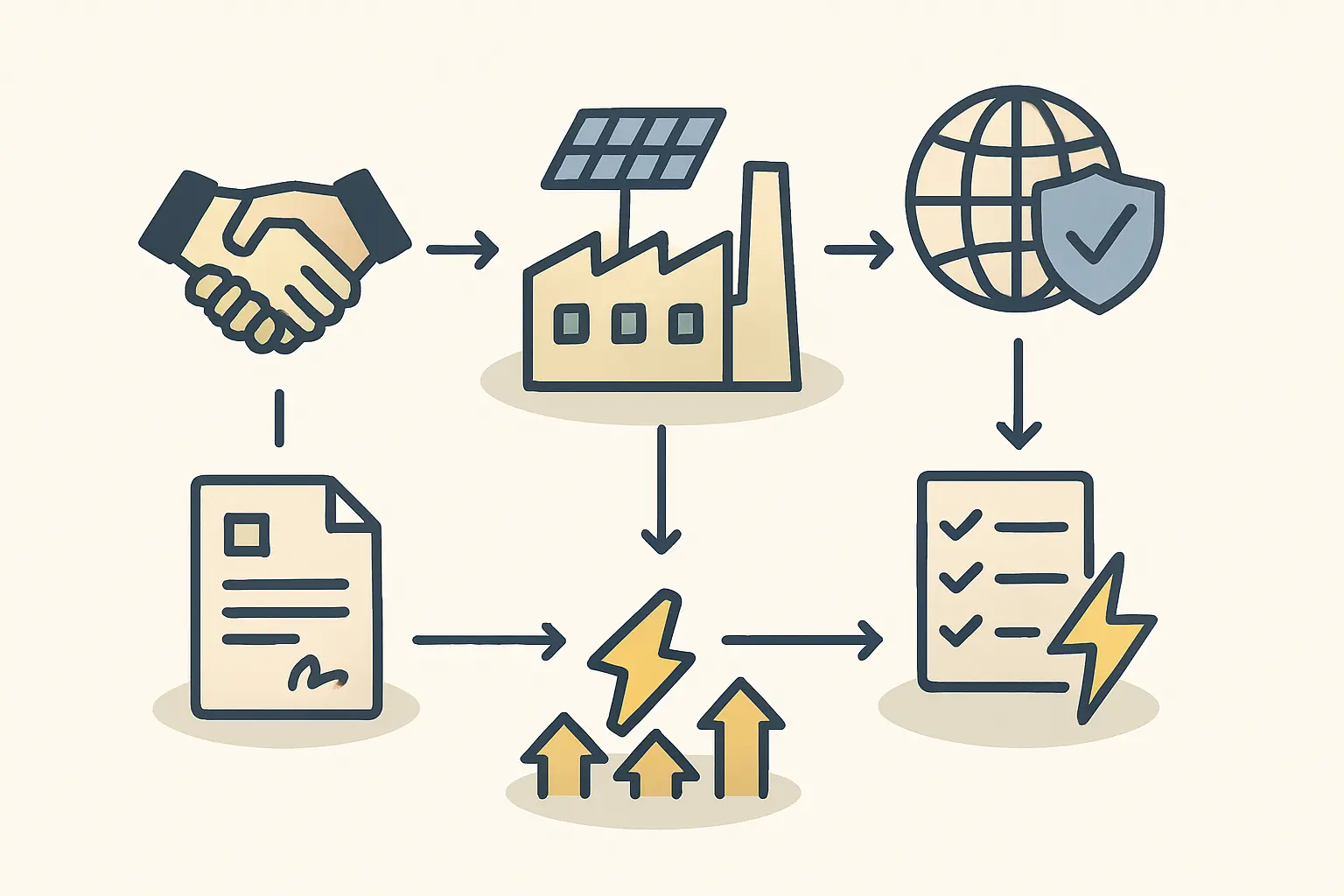

Brunei’s commitment to Islamic principles shapes its governance and economy, with the financial sector being a prime example. The country’s economic roadmap, Wawasan Brunei 2035, aims to diversify away from oil and gas dependency, creating significant opportunities for ventures in renewable energy and manufacturing.

The Brunei Darussalam Central Bank (BDCB) oversees a banking system where Islamic finance is not a niche product but the mainstream. This approach is driven by both cultural alignment and a regulatory preference for financial models that promote risk-sharing and tie financial activities to the real economy. As a result, any investor seeking to establish a significant industrial presence will inevitably engage with Sharia-compliant financing instruments.

Core Principles of Islamic Finance for Industrial Projects

Navigating this environment requires understanding the fundamental principles that distinguish Islamic finance from conventional models. These tenets are not merely rules; they reflect a different philosophy of commerce and investment.

The Prohibition of Interest (Riba)

The most significant distinction is the absolute prohibition of Riba, which refers to any fixed, predetermined return on a loan—the practice commonly known as interest. Instead of charging interest, Islamic banks generate profit through trade and investment activities. For a solar factory project, this means financing will be structured as a partnership, lease, or sale agreement rather than a simple loan.

Asset-Backed Transactions

Every Islamic financial transaction must be linked to a tangible, underlying asset. This principle makes the model particularly well-suited for manufacturing, where financing is needed for physical items such as machinery, buildings, and raw materials.

Consequently, a request for capital is not for money itself but for the acquisition of specific, identifiable assets needed to run the factory. This grounding in real assets inherently reduces speculative risk.

Shared Risk and Reward

The principles of Gharar (excessive uncertainty) and Maysir (speculation or gambling) are prohibited, which encourages financing structures where the bank and the client share the venture’s outcomes.

The financial institution becomes more of a partner than a lender, its returns linked directly to the project’s success. This alignment of interests promotes the long-term viability of the solar manufacturing business.

Common Financing Structures for a Solar Factory

For an investor, these principles translate into specific financing contracts. Several models are well-suited to the diverse capital needs of a solar factory.

Murabaha: For Procuring Machinery and Raw Materials

Murabaha is a cost-plus financing model and one of the most common instruments for asset acquisition. In this structure:

- The entrepreneur identifies the necessary equipment for the turnkey solar manufacturing line.

- The bank purchases the equipment directly from the supplier.

- The bank then sells the equipment to the entrepreneur at a pre-agreed price, which includes the original cost plus a profit margin.

- The entrepreneur repays the bank in installments over a set period.

This structure allows the factory to acquire essential machinery without engaging in an interest-based loan. The bank’s profit comes from the sale transaction, not from lending money.

Ijara: For Leasing Equipment and Facilities

Ijara is analogous to a conventional lease. The bank purchases an asset—such as the factory building or specialized testing equipment—and then leases it to the entrepreneur for an agreed-upon rental fee and duration. At the end of the lease term, ownership of the asset may be transferred to the entrepreneur in a structure known as Ijara wa Iqtina (lease and ownership). This model offers an effective way to manage large capital expenditures and preserve working capital.

Musharaka: For Joint Venture and Partnership Models

Musharaka represents a true partnership model where the bank and the entrepreneur both contribute capital to the solar manufacturing project. While profits are shared according to a pre-agreed ratio, losses are shared in proportion to each party’s capital contribution. This model is ideal for large-scale projects, allowing an investor to share financial risk and leverage the bank’s network and expertise. Proposing a Musharaka agreement requires a comprehensive business plan that clearly demonstrates the project’s profitability and management structure.

Navigating the Process: Key Considerations for Investors

Successfully securing Sharia-compliant financing in Brunei requires a strategic approach.

The Importance of a Detailed Feasibility Study

Because Islamic finance is asset-focused and risk-averse, financial institutions require exceptionally detailed project plans. The feasibility study must clearly outline all tangible assets to be acquired, from production machinery to IT infrastructure. A thorough breakdown of the investment requirements for a solar factory is more than a planning tool—it is a prerequisite for any financing discussion.

Engaging Specialized Advisors

The legal and financial nuances of Sharia-compliant contracts can be complex for the uninitiated. Engaging local legal and financial advisors with expertise in Islamic finance is essential. These experts can help structure the project proposal to meet the requirements of Bruneian banks and ensure all contracts are sound.

Aligning with Wawasan Brunei 2035

Positioning the solar manufacturing project as a direct contributor to Brunei’s economic diversification goals provides a significant advantage. Highlighting how the venture creates local jobs, develops technical skills, and supports the growth of a non-oil export sector can strengthen the financing proposal, making it more attractive to institutions like the Brunei Investment Agency (BIA).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: Is Islamic finance only available to Muslim investors?

A: No. Sharia-compliant financing is available to any investor or business, regardless of their faith, provided the project itself is permissible (i.e., not related to prohibited industries like alcohol or gambling). Solar energy is considered a highly ethical and permissible industry.

Q: Is Sharia-compliant financing more expensive than conventional loans?

A: Not necessarily. While the cost structure is different—based on profit margins or rental fees instead of interest—the overall cost of financing is generally competitive with conventional markets. The final cost depends on the project’s risk profile and the specific financing instrument used.

Q: How long does the approval process typically take?

A: The timeline is comparable to that of conventional project financing. The duration depends on the complexity of the project, the quality of the business plan, and the thoroughness of the due diligence performed by the bank.

Q: Can working capital be financed under this system?

A: Yes. While direct cash loans for working capital are not possible, structures like Murabaha for raw materials or a commodity-based transaction known as Tawarruq can be used to manage short-term liquidity needs.

Conclusion: A Strategic Path to Investment

Financing a solar manufacturing project in Brunei requires navigating a financial system built on Sharia principles. While this may seem unfamiliar at first, it offers a stable, well-regulated framework that strongly supports asset-based industrial ventures.

By understanding core concepts like Riba, Murabaha, and Musharaka, and by preparing a meticulous, asset-focused business plan, an entrepreneur can effectively access the significant pool of capital available in the country. The system’s emphasis on partnership and shared risk can create a more resilient foundation for long-term success, as it aligns the financial institution’s interests with the operational success of the solar factory. For the well-prepared investor, Brunei’s financial landscape is not an obstacle but a strategic opportunity.