An established entrepreneur in Suva—perhaps successful in logistics or construction—sees a clear trend: Fiji’s national commitment to 100% renewable energy by 2030. Pivoting into solar module manufacturing seems like a logical next step, serving both a national goal and a growing regional market.

A preliminary discussion with a commercial bank, however, reveals a common challenge. The bank’s loan officers, accustomed to financing real estate or trade, view a specialized manufacturing facility as a high-risk venture, requiring prohibitive collateral and offering restrictive terms.

This is a familiar scenario for business leaders exploring industrial projects in emerging economies. While commercial banks are essential, their traditional risk models often fail to align with the strategic, long-term nature of renewable energy manufacturing.

Fortunately, an alternative financing ecosystem exists, one specifically designed to support such nation-building projects. This guide explores how to structure a financial model to attract capital from institutions like the Fiji Development Bank (FDB) and the Green Climate Fund (GCF)—organizations that prioritize developmental impact alongside financial returns.

Why Traditional Financing Can Be a Hurdle for Solar Manufacturing

Commercial banks typically evaluate loan applications based on historical cash flows, hard asset collateral, and established market comparables. A new solar module factory presents several challenges to this model:

-

Perceived Technology Risk: Lenders often lack the in-house expertise to accurately assess the technology and operational plan for a solar module assembly line.

-

Lack of Local Precedent: With no other solar factories in the region, banks have no direct comparison for benchmarking risk and potential returns.

-

Mismatched Timelines: A manufacturing plant’s payback period is typically longer than the short-to-medium-term lending cycles favored by many commercial banks.

-

Focus on Purely Financial ROI: A standard loan application has no formal mechanism for valuing critical co-benefits like energy independence, job creation, or carbon emission reductions.

These factors can stall projects that are otherwise viable, simply because of a misalignment between the project’s nature and the lender’s criteria.

A New Landscape of Capital: Development Finance and Climate Funds

Development Finance Institutions (DFIs) and global climate funds operate with a different mandate. They provide “patient capital” to projects that deliver measurable economic, social, and environmental benefits—often in sectors that commercial lenders consider too risky.

For an aspiring solar manufacturer in Fiji, understanding the priorities of these organizations is the first and most critical step toward securing funding.

The Role of the Fiji Development Bank (FDB)

As the nation’s key development financing body, the FDB is mandated to support projects aligned with Fiji’s national development plan. The bank is also an accredited Direct Access Entity for the Green Climate Fund, enabling it to channel international climate finance to local projects.

When assessing a proposal for a solar factory, the FDB looks beyond a simple profit and loss statement. Its evaluation will likely include how the project contributes to:

-

Reducing Fossil Fuel Imports: Decreasing Fiji’s economic exposure to volatile global oil prices.

-

Building Climate Resilience: Strengthening the national energy grid with distributed, renewable power sources.

-

Creating Skilled Employment: Fostering a new high-tech manufacturing sector.

Tapping into the Green Climate Fund (GCF)

The GCF is the world’s largest dedicated climate fund, mandated to support developing countries in their transition to low-emission, climate-resilient development. It frequently co-finances projects with local DFIs like the FDB.

A financial model prepared for the GCF must demonstrate “paradigm-shift potential.” This means showing how the project does more than just generate clean energy; it must prove it can fundamentally alter the country’s economic and energy landscape for the better. Local manufacturing of solar modules, which builds in-country capacity and reduces reliance on imports, is a strong candidate for this classification.

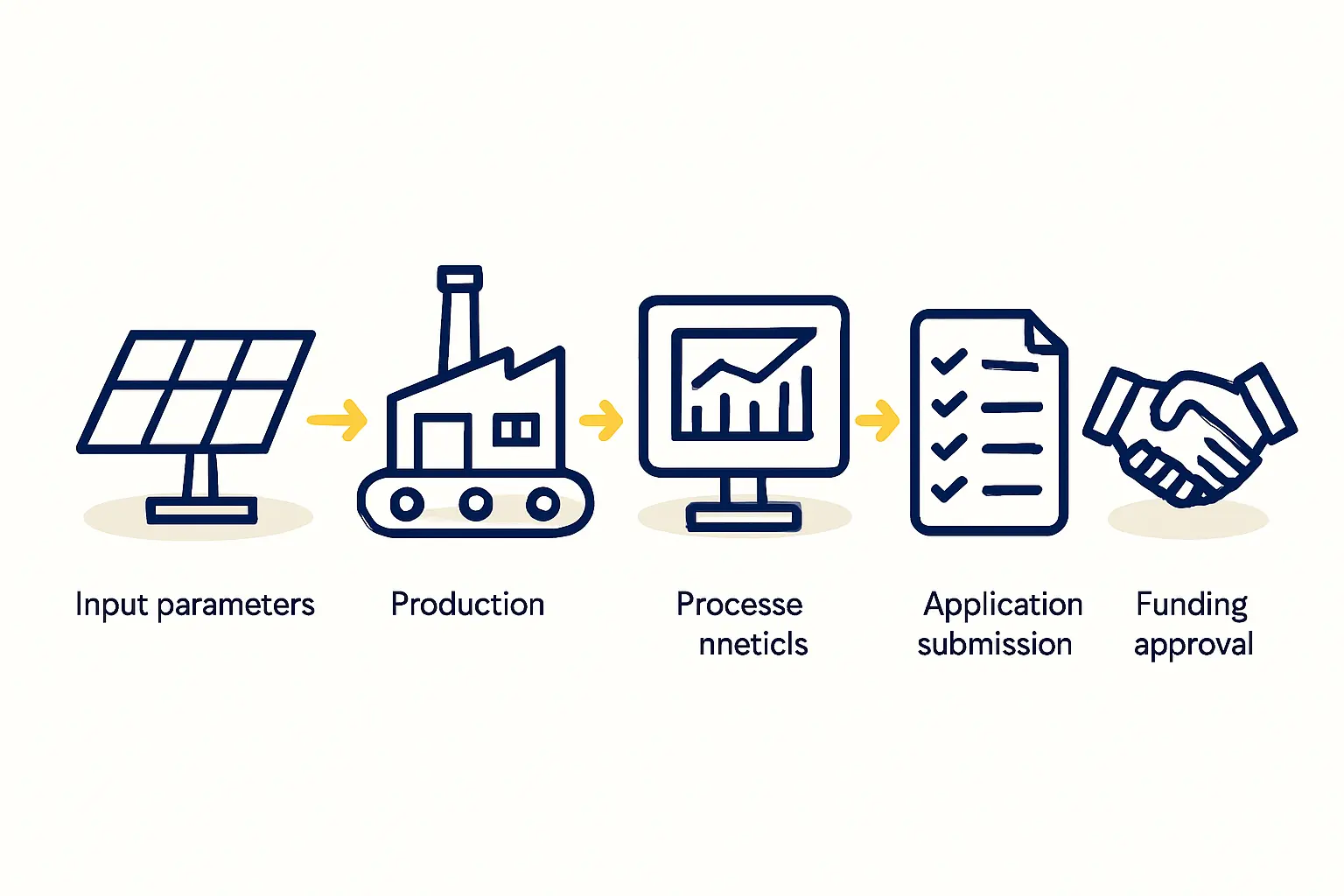

Crafting a Financial Model That Speaks Their Language

To secure capital from DFIs and climate funds, your financial model must evolve from a simple spreadsheet into a comprehensive strategic document. It needs to tell a compelling story, backed by credible data, of how financial investment translates into sustainable development.

Beyond Profit: Demonstrating ‘Co-Benefits’

While profitability is essential for sustainability, it isn’t the only metric that matters. The model must quantify the project’s positive externalities, or “co-benefits.”

-

Environmental Impact: Calculate the estimated tonnes of CO₂ emissions abated annually compared to diesel-generated power.

-

Economic Impact: Project the value of import substitution (no longer needing to buy finished panels from abroad) and the number of direct and indirect jobs created.

-

Social Impact: Detail plans for local workforce training and technology transfer, creating a skilled labor pool for a growing industry.

These are not footnotes; they are core components of the value proposition for a development-focused investor. A compelling business plan for a solar factory will integrate these metrics directly into its executive summary and financial projections.

Key Metrics for a DFI-Ready Financial Model

Your financial projections should be detailed, transparent, and built on conservative assumptions.

-

Capital Expenditure (CapEx): A granular breakdown of all initial costs is essential. This includes the price of solar panel manufacturing machines, shipping, installation, facility construction or retrofitting, and initial raw material inventory. Providing quotes from reputable suppliers adds significant credibility.

-

Operational Expenditure (OpEx): Clearly outline recurring costs, including labor, raw materials (glass, cells, backsheets), utilities, maintenance, and overhead.

-

Revenue Projections: Base these on a thorough market analysis. Who are the target customers—local utility-scale projects, commercial and industrial rooftops, or residential installers? What are realistic market prices and sales volumes?

-

Cash Flow Analysis: A multi-year cash flow projection is critical to demonstrate the project’s long-term viability and its ability to service debt.

-

Alignment with National Goals: The proposal must explicitly reference how it supports Fiji’s national policies, such as its Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) under the Paris Agreement and its goal of 100% renewable energy.

Based on experience from turnkey projects, investors in this space value a business case built on operational reality. For instance, a 25 MW semi-automated assembly line might require an initial investment of USD 5–7 million, occupy a 2,500-square-meter facility, and employ around 40-50 staff members. The financial model must reflect these specific, practical realities.

Navigating the Application Process: Common Pitfalls to Avoid

Securing development finance is a meticulous process. Entrepreneurs new to this landscape often encounter the same obstacles.

-

Inadequate Feasibility Study: A high-level idea is not enough. A “bankable” feasibility study, complete with technical specifications, market analysis, and detailed financial projections, is non-negotiable.

-

Underestimating Local Logistics: The model must account for the realities of operating in a Pacific Island nation, including shipping times for raw materials and potential infrastructure challenges.

-

Failing to Engage Stakeholders: Early engagement with entities like the FDB, relevant government ministries, and potential large-scale customers can strengthen the proposal and demonstrate market validation.

Platforms like pvknowhow.com provide structured educational resources, such as an e-course on factory planning, designed to help entrepreneurs prepare these essential documents to a professional standard.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the primary difference between a commercial loan and DFI financing?

A commercial loan is assessed primarily on its risk and financial return to the bank. DFI financing is a “double bottom line” investment, assessed on both its financial viability and its contribution to measurable sustainable development goals. As a result, terms like loan tenure and interest rates are often more favorable.

Do I need a technical partner to apply for these funds?

While not always mandatory, having a credible technical partner significantly strengthens an application. It demonstrates to non-technical financiers that the operational plan is sound, the technology is appropriate, and the project has a high probability of success.

How long does the funding process typically take?

The process is generally longer and more rigorous than for a standard commercial loan, often taking six to 18 months. The due diligence is extensive, covering technical, financial, environmental, and social aspects of the project.

Can I get 100% funding from these institutions?

It is highly unlikely. DFIs and climate funds almost always require the project sponsor to contribute a significant portion of the equity. This demonstrates commitment and ensures all parties have a vested interest in the project’s success. A typical requirement is for the entrepreneur to fund 20-30% of the total project cost.

Your Next Steps in Securing Capital

For entrepreneurs in Fiji and the wider Pacific region, the path to financing a solar module factory does not run through conventional banking alone. The true opportunity lies in aligning a commercially sound project with the strategic objectives of national and international development financiers.

This requires a shift in perspective—from building a purely for-profit enterprise to creating a strategic national asset. By developing a financial model that quantifies both profit and purpose, you can unlock access to the patient, supportive capital needed to turn the vision of local solar manufacturing into a reality.