Entrepreneurs exploring the solar manufacturing sector often begin with standard financial templates. They project revenue based on global module prices and estimate capital expenditure for machinery. Yet, a business plan that looks profitable on paper can quickly become unviable when faced with the unique economic realities of a specific market. An investor planning a factory in Guinea-Bissau, for instance, will find that a model based on European or Chinese cost structures is fundamentally flawed.

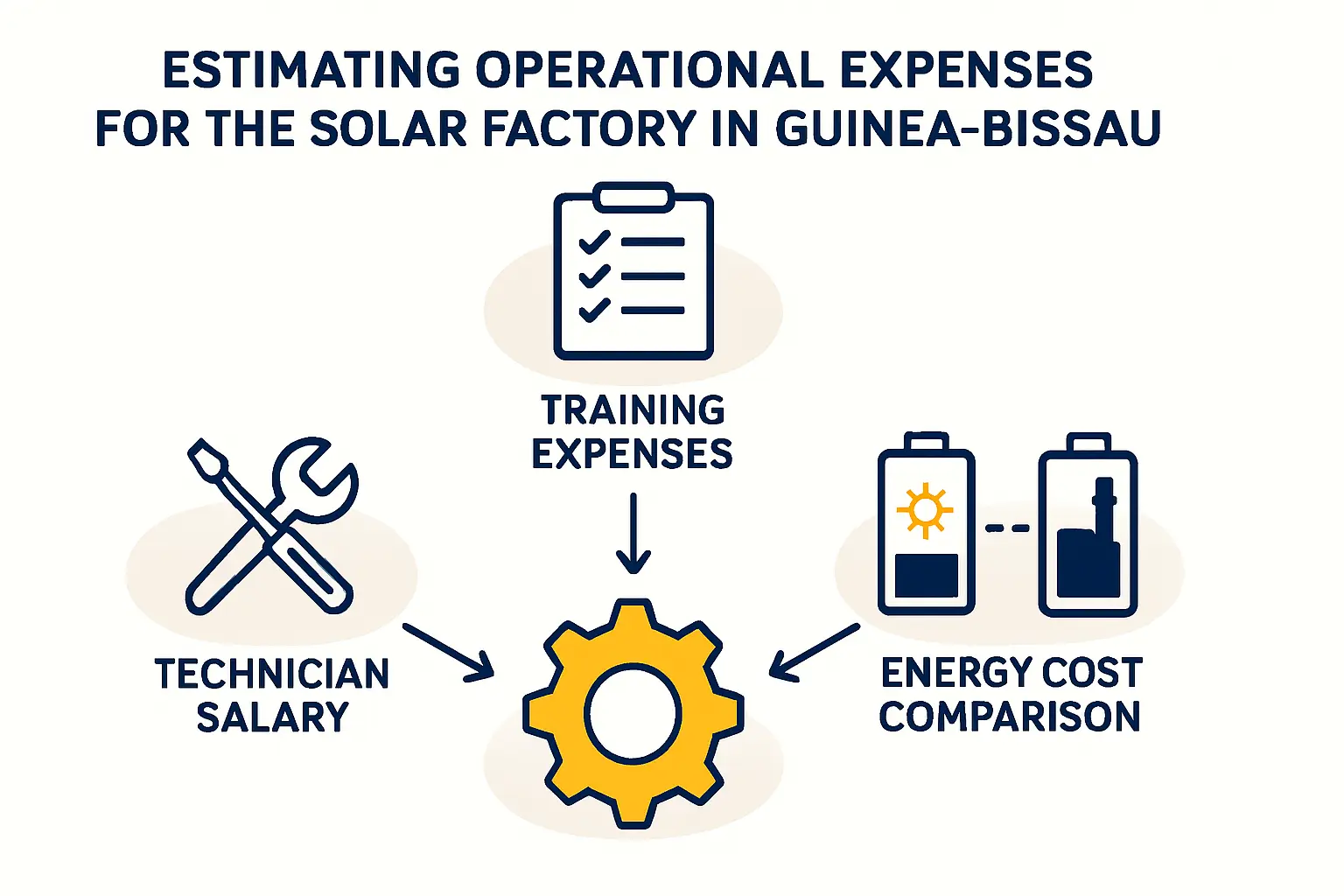

The success of a solar manufacturing venture hinges not just on the technology, but on a granular understanding of local operating expenses. Variables such as technician salaries, workforce training, and, crucially, the cost and reliability of energy can dramatically alter a project’s financial viability. This article breaks down how to build a more realistic financial model for a solar factory in Guinea-Bissau by focusing on these decisive local factors.

Why Generic Financial Models Fail in Specific Markets

A financial model is only as reliable as the data it uses. While the cost of a turnkey solar manufacturing line may be globally comparable, the daily expenses of running that line are hyper-local. Relying on international averages for operating costs is a common and costly mistake for new market entrants.

For a market like Guinea-Bissau, the analysis must dig deeper in three particular areas:

-

Labor Costs and Availability: Labor expenses extend far beyond wages. They include recruitment costs, investment in technical training for a nascent industry, and the potential need for expatriate oversight during the initial phases.

-

Energy Tariffs and Reliability: The factory’s largest operational cost after raw materials is often electricity. The price and stability of the national grid directly impact production uptime and profitability.

-

Logistics and Importation: The cost of moving raw materials from the port of Bissau to the factory and shipping finished modules can differ significantly from estimates based on other regions.

A robust financial forecast must replace generic assumptions in these areas with well-researched local data.

Deconstructing Operating Expenses (OPEX) for Guinea-Bissau

To build a viable business case, an entrepreneur must move from high-level estimates to a detailed, ground-up analysis of operational expenditures.

Analyzing Local Labor Costs

While wage levels in Guinea-Bissau may appear advantageous compared to developed nations, a comprehensive labor budget includes several components beyond basic salaries. For a typical 50 MW factory operating a single shift, the workforce might number around 25-30 employees.

Key Considerations for the Labor Budget:

Skilled Technicians: The core of the production team will require specific training. While general labor may be readily available, technicians capable of operating and maintaining sophisticated equipment used in the solar module manufacturing process will almost certainly need to be trained. Budgeting for this initial training, including potential instruction from equipment suppliers, is essential. Based on data from similar emerging markets, allocating 15-20% of the first year’s labor budget to training is a prudent measure.

Engineering and Management: At least one senior production engineer and a plant manager are crucial. Initially, it may be necessary to fill these roles with expatriate staff who have direct experience in solar manufacturing. The cost for an expatriate manager can be 5-10 times that of a local equivalent, a significant factor in the early years of operation.

Salary Benchmarking: A detailed model must project salaries based on local benchmarks. For example:

- Production Line Operator/Technician: $250 – $450 USD per month

- Local Junior Engineer: $600 – $900 USD per month

- Expatriate Senior Engineer/Plant Manager: $5,000 – $10,000 USD per month (plus housing and benefits)

This detailed approach provides a much clearer picture of true labor costs than a simple headcount multiplied by an average wage.

The Critical Impact of Energy Tariffs

A solar module factory is an energy-intensive operation. The lamination machine, in particular, consumes a significant amount of electricity. The cost and reliability of the power supply are paramount to financial success.

In Guinea-Bissau, an investor has three primary options for powering the factory, each with distinct financial implications.

-

Grid Supply (EAGB): The national utility, Electricidade e Águas da Guiné-Bissau (EAGB), offers the simplest connection. However, the model must account for high commercial tariff rates (estimated at $0.25-$0.35 USD/kWh) and, importantly, potential grid instability. Frequent power outages can halt production, leading to material waste and lost revenue that far exceed the electricity cost itself.

-

Diesel Generation: Using on-site diesel generators provides independence from the grid but introduces fuel price volatility and high maintenance costs. With diesel prices subject to global markets and local supply chains, the Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE) from a generator can easily exceed $0.40 USD/kWh, making it one of the most expensive and least sustainable options.

-

On-site Solar and Storage: A compelling alternative is to power the solar factory with its own solar and battery storage system. While this requires a higher initial capital investment, it provides a stable, predictable energy source with a low long-term cost (an LCOE potentially below $0.15 USD/kWh). This strategy hedges against rising utility tariffs and fuel costs, offering a significant competitive advantage. The choice of energy-efficient machinery is even more important here, as selecting the right solar manufacturing equipment can reduce the required size of the on-site power system.

For any serious investor, a sensitivity analysis showing how profit margins change with different energy scenarios is not just an academic exercise—it is an essential risk management tool.

Factoring in Other Local Variables

Beyond labor and energy, a complete financial model must incorporate other costs specific to the operating environment.

Logistics and Supply Chain Costs

Because the raw materials for solar module manufacturing—such as solar cells, EVA, glass, and backsheets—are imported, the financial model must include realistic figures for:

- Port handling fees and customs clearance at the Port of Bissau.

- Inland transportation costs from the port to the factory site.

- Buffer stock inventory costs to mitigate potential supply chain delays.

Based on experience from turnkey projects in Africa, logistics can add between 8% and 15% to the landed cost of raw materials, a figure that should be explicitly budgeted for.

Import Duties and Regulatory Frameworks

Government policies will also have a profound impact. It is crucial to research and confirm:

- Import duties on manufacturing equipment.

- Tariffs on raw materials versus finished solar panels.

- Any tax incentives or special economic zones available for new industrial ventures.

Engaging local legal and financial advisors early in the planning process is vital to ensuring the model reflects the true regulatory landscape.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: How much capital is needed to start a small solar factory in Guinea-Bissau?

A: For a semi-automated 20-50 MW assembly line, the initial capital for machinery, setup, and training typically ranges from $1 million to $3 million USD. This does not include the building or working capital for raw materials. A detailed financial model is required to determine the full investment.

Q: Can a factory be profitable if it relies on a diesel generator for power?

A: While technically possible, it is extremely challenging. The high and volatile cost of diesel fuel puts the factory at a major cost disadvantage compared to competitors with access to cheaper power. Production costs could be 20-30% higher, severely impacting margins.

Q: How long does it take to train local staff to operate the machinery?

A: With a structured training program led by experienced engineers from the equipment supplier, a local team can typically be trained to operate the line proficiently within four to six weeks. Ongoing skill development is recommended.

Q: Is it better to start with a fully automated or semi-automated line?

A: For new markets like Guinea-Bissau, a semi-automated line is often recommended. It requires a lower initial investment and creates more local jobs. It also offers more flexibility and is less complex to maintain, which is an advantage where highly specialized technical support may not be immediately available.

Ultimately, creating a successful solar manufacturing business in Guinea-Bissau requires moving beyond generic templates. A detailed, localized financial model that accurately reflects the on-the-ground costs of labor, energy, and logistics is the first and most critical step. This foundational work transforms a speculative idea into a credible, data-driven investment plan ready for execution.