The idea of manufacturing solar panels in a land known more for its glaciers and volcanoes than its sunlight may seem counterintuitive. Yet, for any business professional, Iceland serves as a fascinating case study in strategic planning. Its access to abundant, low-cost geothermal and hydroelectric power provides a unique advantage for energy-intensive manufacturing. This opportunity, however, is balanced by a significant challenge: as an island nation in the North Atlantic, its entire manufacturing operation hinges on mastering global and local logistics.

While this article focuses on Iceland, the principles discussed apply to any entrepreneur considering a manufacturing facility in a location with complex logistical pathways, whether on an island or in a landlocked region far from major shipping hubs. Success depends not just on production technology, but on the disciplined management of bringing materials in and shipping finished products out.

The Global Journey of Solar Components

A solar panel factory does not create its components from scratch; it is primarily an assembly operation that relies on a global supply chain. The vast majority of essential raw materials originate in Asia, with manufacturing powerhouses like China, Taiwan, South Korea, and Malaysia leading production.

Key materials imported for a standard solar module assembly line include:

- Silicon Wafers: The heart of the solar cell.

- Solar Glass: Specially tempered and coated glass for the front of the panel.

- Encapsulant Films (EVA/POE): Polymers used to laminate the components together.

- Backsheets: The protective rear layer of the module.

- Junction Boxes: Electrical enclosures on the back of the panel.

- Aluminum Frames: The structural border of the finished module.

Each of these components has its own supply dynamics, and understanding the total landed raw material costs is critical for building a viable financial model. The price paid to the supplier is only the beginning of the story.

Mapping the Inbound Logistics: From Asia to the North Atlantic

The journey for these materials from an Asian port to a factory in Iceland is a multi-stage process that demands careful planning. Standard 40-foot shipping containers are the workhorses of this supply chain.

The typical shipping route involves two main legs:

-

Primary Leg: A long-haul sea voyage from a major Asian port to one of Northern Europe’s primary container hubs, such as Rotterdam in the Netherlands or Hamburg in Germany. This leg alone typically takes 30 to 45 days.

-

Feeder Leg: From the European hub, the containers are transferred to smaller feeder vessels for the final journey to Reykjavik, Iceland. This second leg adds another 3 to 7 days.

In total, entrepreneurs must plan for a transit time of 35 to 52 days from the time a container leaves the supplier’s port until it arrives in Iceland. This timeline doesn’t account for potential delays in customs, port congestion, or weather.

A critical factor for any business plan is the high volatility of shipping costs. A single 40-foot container from Asia to Europe could cost anywhere from $2,000 to $4,000 before 2020. During the supply chain disruptions of the pandemic, these costs soared as high as $20,000. Today, the market has settled, but rates of $4,000 to $8,000 are not uncommon. This variability directly impacts production costs and requires careful, constant monitoring.

The Critical Role of Inventory Management in Remote Manufacturing

Given the long and variable lead times for inbound materials, a Just-in-Time (JIT) inventory strategy is highly impractical and risky for an Icelandic solar factory. A single delayed shipment could halt the entire production line for weeks, leading to significant financial losses and an inability to meet customer orders.

The solution lies in maintaining a robust buffer stock. For critical components sourced from Asia, holding two to three months’ worth of inventory on-site is a prudent safety net. This strategy ensures production continuity but comes with a significant trade-off: it ties up a substantial amount of working capital in stored materials. This financial requirement must be factored into the initial investment and operational budget from day one. Proper warehousing and inventory management systems are not optional extras; they are foundational to the factory’s survival.

Outbound Logistics: Exporting Finished Modules to Global Markets

While inbound logistics present a challenge, outbound logistics represent a strategic opportunity for a factory in Iceland. Its geographic position makes it uniquely suited to serve two of the world’s major solar markets: Europe and North America.

To Europe: Shipping finished modules to major European ports is relatively quick and efficient, taking approximately 3 to 7 days.

To North America: Reaching East Coast ports in the United States and Canada takes around 10 to 14 days.

Export shipping costs are generally more stable than the volatile Asia-Europe routes. A container to Europe might cost between $1,500 and $3,000, while one to North America could be in the range of $2,500 to $4,500.

Crucially, Iceland’s membership in the European Economic Area (EEA) grants its exports tariff-free access to the entire European Union market—a powerful competitive advantage. This allows ‘Made in Iceland’ modules to compete on a level playing field with those produced within the EU, potentially avoiding import duties levied on panels from other regions.

Navigating Local Challenges and Mitigating Risks

The final mile of the supply chain—from the port in Reykjavik to the factory itself—also requires careful planning. Iceland has a well-maintained road network, particularly in potential industrial areas. However, severe winter weather can occasionally cause road closures and transportation delays, reinforcing the need for adequate on-site inventory.

To manage the array of logistical risks, a new manufacturer should implement several key strategies:

- Build Strong Logistics Partnerships: Working with an experienced freight forwarder who understands North Atlantic shipping routes is essential.

- Forward-Book Freight: Where possible, booking container capacity in advance can help secure space and manage cost volatility.

- Factor Logistics into the Business Model: The entire business plan for solar manufacturing must be built around the realities of the supply chain, from cash flow planning for inventory to pricing models that account for fluctuating freight costs.

Based on experience from J.v.G. Technology GmbH turnkey projects, integrating logistics planning from the earliest stages is vital for success. A turnkey production line is not merely about the machines on the factory floor; it is about the end-to-end system that feeds them and delivers their output to market.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Why would an entrepreneur consider Iceland for a solar factory?

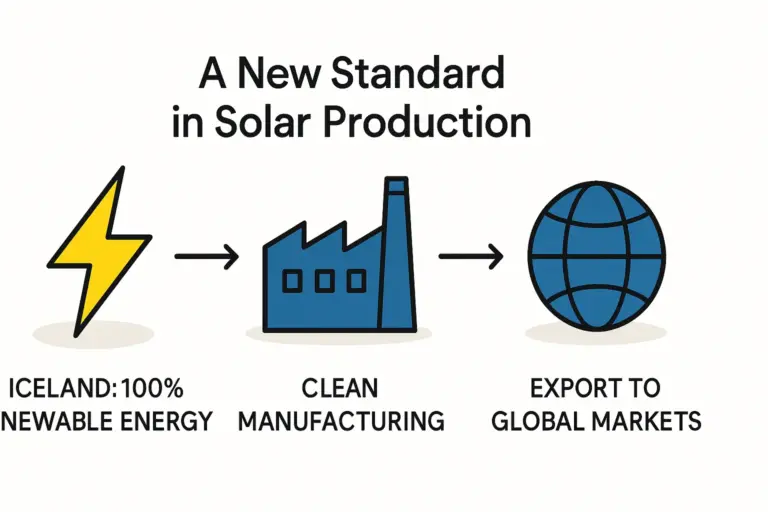

Beyond the logistical challenges, Iceland offers compelling advantages: 100% renewable and low-cost electricity for production, a stable political and economic environment, and tariff-free access to the lucrative EU market. This combination can create a strong business case.

How much does logistics add to the final cost of a solar module?

This figure varies significantly, depending heavily on prevailing freight rates. It is a major cost component that can range from a few percent to over ten percent of the final module cost, especially during periods of high shipping prices. It must be carefully modeled in the financial projections.

What is the single biggest logistical mistake a new manufacturer can make?

The most common and costly mistake is underestimating inbound lead times and failing to maintain an adequate buffer stock of raw materials. This oversight can lead to expensive production stoppages that disrupt operations and damage customer relationships.

Can a smaller factory (e.g., 50 MW) manage such a complex supply chain?

Absolutely. The principles of supply chain management are scalable. A smaller operation can navigate these complexities through diligent planning, strong partnerships with logistics providers, and a clear understanding of the working capital required for inventory.

Conclusion: From Logistical Challenge to Strategic Advantage

Operating a solar module factory from an island location like Iceland presents a unique set of supply chain challenges that demand disciplined, proactive management. Long inbound lead times from Asia necessitate a capital-intensive inventory strategy, and variable shipping costs require careful financial oversight.

With proper planning, however, these challenges can be managed and the location itself turned into a strategic advantage, offering preferential access to key European and North American markets. For the prepared entrepreneur, mastering logistics is not just an operational necessity; it is the key that unlocks a unique competitive position in the global solar industry.