For an entrepreneur in an atoll nation, building a local solar module factory is a logical response to a dual challenge. High electricity costs, fueled by a near-total dependence on imported diesel, create a substantial economic burden. At the same time, the increasing frequency and intensity of tropical cyclones pose a direct threat to any significant infrastructure investment. This raises a critical question: how do you build a facility for the future of energy in a location so exposed to nature’s most powerful forces?

This is far from a theoretical problem. The Pacific and Indian Oceans are home to nations where energy independence is a national security issue, yet a Category 5 cyclone remains a realistic operational risk. The solution lies in engineering for resilience from the ground up.

This guide outlines the fundamental structural and layout considerations for establishing a solar module factory capable of withstanding extreme weather events in atoll environments. It focuses on the key engineering principles that transform a potential vulnerability into a calculated, manageable risk.

The Dual Imperative: Energy Independence and Climate Resilience

Atoll nations face a unique paradox. They possess some of the world’s best solar irradiation, yet they remain tethered to volatile global fuel markets. A local solar module manufacturing plant addresses this directly:

-

Reducing Energy Costs: On-site manufacturing can significantly lower the cost of solar panels by eliminating international shipping and import tariffs for finished goods.

-

Creating Skilled Employment: A factory introduces technical jobs and fosters a new industrial sector.

-

Strengthening the Grid: Locally produced modules can support the development of resilient, decentralized power grids, crucial for post-storm recovery.

However, the very climate change that makes solar energy a necessity also amplifies the risks. A factory must be designed with a ‘doomsday scenario’ in mind: a direct impact from a major cyclone, accompanied by a significant storm surge. Standard industrial building practices are simply inadequate in this context.

Foundation and Structural Integrity: Building on Coral Geology

The first line of defense is the building’s foundation and core structure. Atoll geology, typically consisting of porous coral sand and limestone, presents unique challenges that require specialized engineering.

Foundation Design for Stability and Elevation

The ground itself is often unstable and permeable. A robust foundation is non-negotiable.

-

Reinforced Concrete Slab: A monolithic, reinforced concrete slab foundation is often the most practical approach. This design distributes the building’s weight over a large area, providing stability on less-compacted soil. The slab must be engineered with deep, integrated footings to anchor the structure firmly.

-

Piling: In areas with particularly poor soil quality or a high water table, deep-driven piles may be necessary. These piles transfer the structural load down to a more stable layer of bedrock or compacted coral, bypassing the weak upper layers of sand.

-

Elevated Floor Level: Elevating the entire factory floor is a critical defense against storm surge. A typical specification, based on J.v.G. turnkey projects in coastal regions, sets the finished floor level at least 1.5 to 2 meters above the highest recorded high tide or storm surge mark. This simple measure can prevent catastrophic water damage to sensitive equipment.

The Building Envelope: A Shield Against Extreme Wind and Water

The building’s roof and walls—its ‘envelope’—are the primary defense protecting millions of dollars of manufacturing equipment from a cyclone. The design must prioritize aerodynamic performance and brute-force resistance.

Wind Load Engineering

The structure must be rated to withstand the wind speeds of a Category 5 cyclone, which can exceed 250 km/h (157 mph).

-

Reinforced Concrete Walls: Poured and reinforced concrete or concrete block walls offer superior mass and impact resistance against flying debris.

-

Steel Superstructure: A heavy-gauge, galvanized steel frame with robust cross-bracing provides the necessary structural skeleton. All connections must be bolted and welded to exceed standard code requirements.

-

Roof Design: A low-pitch or curved hip roof is more aerodynamic than a flat or gabled roof, reducing the immense uplift forces generated by extreme winds. Roofing materials must be mechanically fastened—not just attached with adhesives—with every panel secured directly to the steel purlins below. Specialized cyclone-rated fasteners are essential.

The integrity of the building envelope is paramount. Even a small breach can lead to internal pressurization, which can blow the roof off from the inside. All doors, windows, and ventilation openings must be fitted with certified cyclone shutters.

Strategic Factory Layout for Risk Mitigation

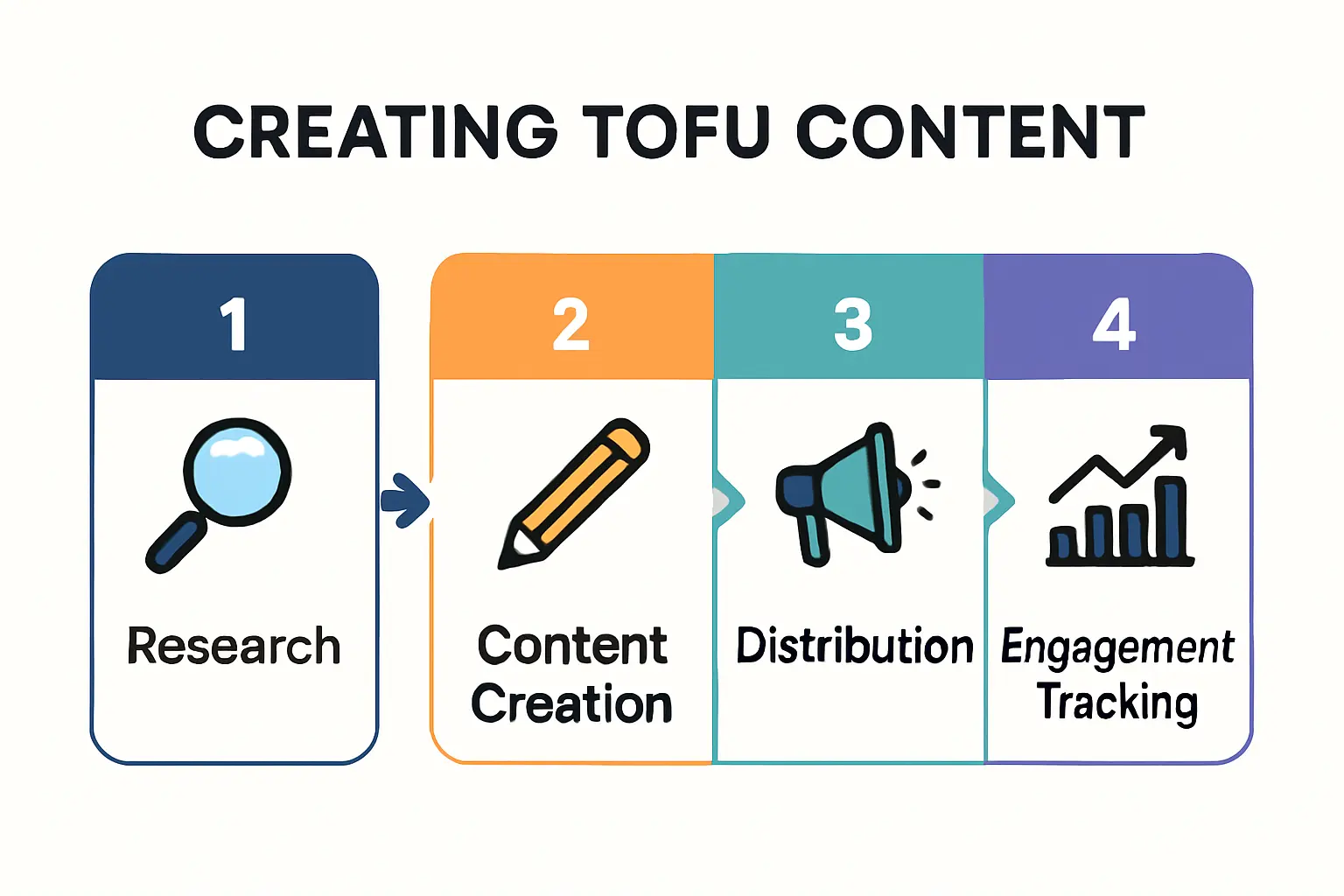

The organization of the interior space is as important as the structure itself. A well-designed layout can minimize damage and expedite a return to operation even if the building’s outer defenses are partially breached. The logical flow of solar panel manufacturing machines must be balanced with risk mitigation.

Protecting High-Value Assets

The core principle is to create zones of protection.

-

Centralized Core: The most expensive and sensitive equipment, such as the laminator and cell stringer, should be located in the factory’s core, well away from exterior walls and potential points of failure.

-

Material Storage: Raw materials like solar glass and EVA film should be stored in designated, well-secured areas away from large doors. A single broken door can allow wind and rain to destroy an entire inventory of materials.

-

Internal Drainage: The floor should be designed with a subtle grade, sloping towards integrated channel drains. Should water enter from roof damage or a storm surge exceeding the floor height, this system can rapidly channel it out of the building, protecting machine bases from prolonged immersion.

Planning the layout with these considerations from the outset is far more cost-effective than attempting to retrofit a standard design. Understanding the costs to start a solar panel factory must include this resilience-focused engineering premium.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: What are the most critical building codes to consider for a cyclone-prone region?

A1: Always consult and exceed local building codes. However, international standards such as the International Building Code (IBC) and ASCE 7 (‘Minimum Design Loads for Buildings and Other Structures’) provide a robust framework for wind load and structural design that is globally recognized and respected by insurers and financiers.

Q2: How much does a cyclone-resistant design add to the overall construction cost?

A2: While variable, budgeting for an additional 15-25% on the civil works and building construction costs is a realistic estimate. This premium covers higher-grade materials, specialized engineering, and more robust foundation work. It should be viewed as a critical insurance policy against total loss.

Q3: Is it possible to retrofit an existing building for solar module manufacturing in these regions?

A3: Retrofitting is possible but often more complex and expensive than a new build. A full structural analysis is required to determine if the existing foundation, frame, and roof can be reinforced to meet cyclone-rated standards. In many cases, the cost of retrofitting approaches that of new construction, making a purpose-built facility a more reliable long-term investment.

Q4: What is the first practical step in planning such a facility?

A4: The first step is a professional site feasibility study. This involves a geotechnical survey to analyze soil conditions, a hydrological study to assess flood and storm surge risk, and an analysis of local logistics and infrastructure. This data forms the bedrock of any credible engineering design and business plan. A structured approach, such as that provided by the pvknowhow.com online course, can guide investors through these initial planning stages.

Conclusion: Engineering for a Resilient Future

Building a solar module factory in an atoll nation is an act of strategic foresight. It directly addresses the intertwined challenges of energy security and climate change. The environmental risks are significant, but they are not insurmountable. Through diligent planning, specialized engineering, and a design philosophy that prioritizes resilience over minimum cost, it is entirely feasible to construct a facility that can both withstand extreme weather and serve as a cornerstone of the nation’s sustainable energy future. With a structured and expert-led approach, these environmental challenges can be successfully navigated, turning a high-stakes vision into a durable reality.