For many entrepreneurs, the idea of manufacturing in a remote island nation seems counterintuitive. Long supply chains, high operational costs, and scarce skilled labor are significant hurdles.

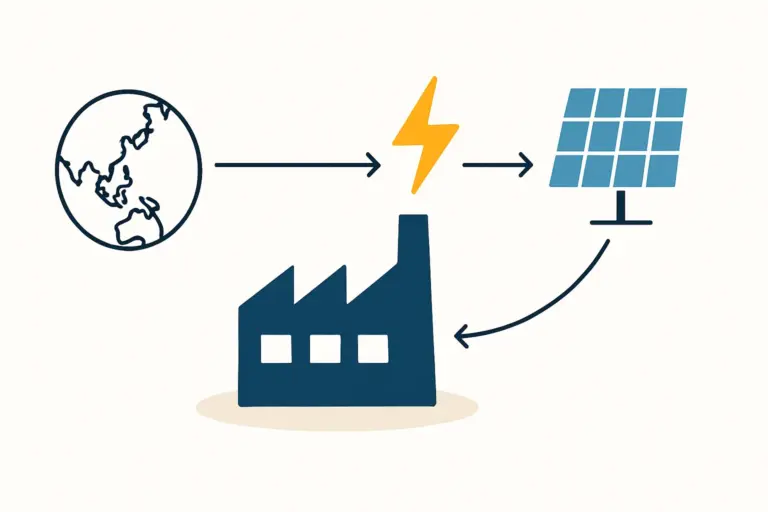

Yet in the Republic of the Marshall Islands (RMI), these very disadvantages create a compelling business case for local solar panel production. With some of the highest electricity prices in the world—driven by a near-total reliance on imported diesel—the RMI presents a unique landscape where local manufacturing can thrive by solving a critical local problem.

This analysis outlines the key financial considerations for establishing a micro-scale (5–10 MW) solar module factory in the RMI, covering the capital expenditures, operational costs, and revenue dynamics that define this challenging but promising market.

Understanding the Unique Economic Context of the RMI

A financial model is only as reliable as the assumptions it is built on. For the Marshall Islands, standard industry metrics from Europe or Asia are simply insufficient; the business case must be grounded in local realities.

-

The Diesel Dependency: The primary driver for solar adoption in the RMI is economic necessity. With electricity costs frequently exceeding $0.40 USD per kWh, energy is a major expense for businesses and households alike. This high cost, directly tied to volatile global oil prices, creates strong, pre-existing demand for any technology that can offer stable, lower-cost power. A local solar factory directly addresses this immediate and pressing need.

-

Logistics and Import Tariffs: As a remote Pacific nation, importing all machinery and raw materials means substantial shipping costs and long lead times. Import duties on raw materials can also significantly inflate the bill of materials (BOM). A successful financial model must accurately account for these inflated supply chain costs, which are a major hurdle to achieving price competitiveness.

-

Labor and Skill Development: While a local labor force is available, specialized technical skills in solar manufacturing are not. The budget must include comprehensive training programs, often requiring expert technicians from abroad to be on-site for an extended period during setup and the initial operational phase.

Capital Expenditures (CapEx): The Initial Investment

Capital expenditures represent the one-time costs of establishing the production facility. For a 5–10 MW line, these costs are manageable but demand careful planning, particularly around logistics.

Core Production Machinery

The heart of the factory is the production line itself. For a semi-automated 10 MW facility, essential equipment includes a cell stringer, bussing and layup stations, an EL tester, a laminator, a framing machine, and a final performance tester (sun simulator). A complete line of this scale, sourced from reliable suppliers, typically requires an investment between $1.5 million and $2.5 million USD. Accurate budgeting at this stage requires a detailed understanding of solar manufacturing equipment.

Building and Infrastructure

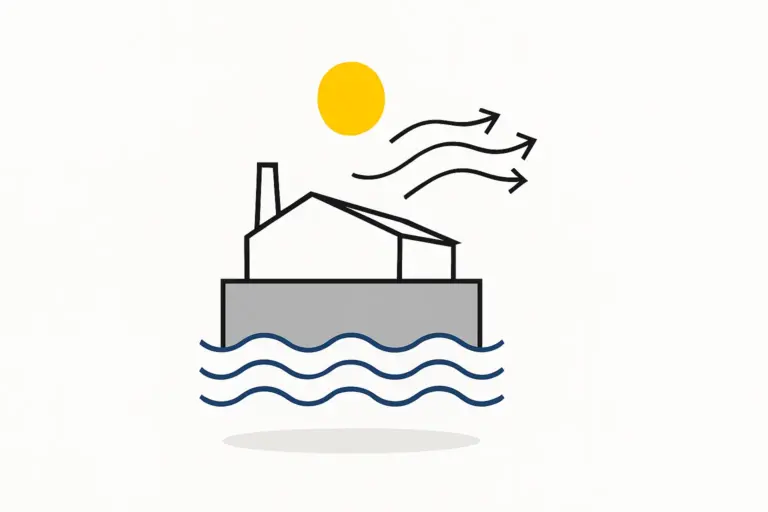

A 10 MW production line requires a facility of approximately 2,000–2,500 square meters to house the line itself, raw material storage, and finished goods warehousing. Whether constructing a new building or retrofitting an existing one, the costs must be tailored to local construction rates in Majuro or Ebeye. The facility must be climate-controlled to protect sensitive materials like EVA film from the high humidity of the tropics.

Ancillary Costs: Freight, Installation, and Training

For a location like the RMI, these ‘soft costs’ can be substantial. Freight charges for multiple 40-foot containers from Asia or Europe can add significantly to the machinery budget. The costs of flying in, housing, and compensating expert engineers for installation, commissioning, and staff training over several weeks must also be factored into the initial CapEx. Based on experience from J.v.G. Technology GmbH turnkey projects in other remote markets, these ancillary costs can sometimes amount to 20-30% of the total equipment cost.

Operational Expenditures (OpEx): The Day-to-Day Costs

Once the factory is operational, ongoing costs will determine its long-term viability. In the RMI, energy and materials are the most critical OpEx variables.

Raw Materials (Bill of Materials – BOM)

The BOM includes all the components required to assemble a solar module: solar cells, glass, EVA encapsulant, backsheets, aluminum frames, and junction boxes. Each of these items will be subject to international shipping costs and local import duties. Establishing reliable supply chains and optimizing inventory management are essential to controlling these costs, as the complete solar panel production process relies on a consistent inflow of these materials.

Energy Costs: The Diesel Generator Factor

Ironically, one of the largest operational expenses for a solar factory in the RMI will be its own electricity bill. The lamination machine, in particular, is energy-intensive. Running the factory on diesel-generated grid power directly exposes the business to the very problem it aims to solve.

A key strategic opportunity lies in powering the factory with its own solar panels. A rooftop or ground-mounted solar array, coupled with a battery storage system, can drastically reduce energy OpEx and insulate the business from fuel price volatility. It also serves as a powerful, real-world demonstration of the product’s value.

Labor and Staffing

A semi-automated 10 MW line typically requires a workforce of 25 to 30 employees, including line operators, quality control technicians, maintenance staff, and administrative personnel. While local wage rates may be lower than in developed countries, the investment in training is higher. A sustainable operation will depend on building a skilled local team capable of running and maintaining the machinery independently over the long term.

Revenue Projections and Market Potential

The factory’s financial viability hinges on its ability to sell its output at a competitive and profitable price.

Local Demand vs. Export

The primary market is domestic. The factory can supply modules to:

- Government and Utility Projects: Helping the RMI meet its renewable energy targets.

- Commercial Businesses: Offering a way to reduce high operating costs from electricity.

- Residential Customers: Providing energy independence.

By manufacturing locally, the business can offer faster delivery, local technical support, and products tailored to marine environments. While exporting to neighboring Pacific Island nations is a possibility, the initial business model should focus on dominating the local market, where the factory has a clear logistical advantage over foreign importers. Validating these market assumptions begins with developing a robust business plan for solar manufacturing.

A Sample Financial Snapshot (5 MW Line)

To illustrate the financial dynamics, consider a simplified model for a 5 MW facility.

| Metric | Estimated Value (USD) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Total Capital Expenditure | ~$1.8 Million | Includes machinery, shipping, and installation. |

| Annual Raw Material Costs | ~$1.6 Million | Assumes a cost of ~$0.32/Wp, including freight. |

| Annual Labor & Overhead | ~$0.6 Million | Covers salaries, energy, rent, and maintenance. |

| Total Annual OpEx | ~$2.2 Million | |

| Potential Annual Revenue | ~$2.25 Million | Assumes 100% of 5 MW capacity is sold at $0.45/Wp. |

This initial model highlights the tight margins. Profitability will depend on securing favorable material costs, maximizing production efficiency, and controlling energy consumption.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

-

How long does it take to set up a 10 MW solar factory?

From equipment ordering to full commissioning, a realistic timeline is between 9 and 12 months. This includes shipping, building preparation, installation, and staff training. -

Is government support necessary for a factory in the RMI to be profitable?

While not strictly necessary, government support—in the form of tax incentives, waivers on import duties for raw materials, or long-term power purchase agreements—can significantly de-risk the investment and accelerate the path to profitability. -

Can a factory in the RMI compete with modules imported from China?

Competing purely on the per-watt price is challenging. The competitive advantage lies in other factors: avoiding import tariffs on finished modules, immediate local availability (no international shipping delays for customers), local warranty support, and creating local employment. -

What is the biggest unforeseen cost for new investors in this sector?

For remote locations, the most commonly underestimated costs relate to logistics and the time required to develop a fully independent local technical team. Budgeting generously for freight contingencies and a comprehensive, multi-month training program is essential.

Conclusion: Your Path Forward

Establishing a solar module factory in the Republic of the Marshall Islands is not a conventional venture, but it addresses an urgent, high-value problem. The high local cost of energy creates a powerful, built-in demand for the product. Success, however, is not guaranteed. It requires a meticulous financial model that honestly assesses the high costs of logistics and energy while leveraging the unique advantages of local production.

For entrepreneurs exploring this opportunity, the first step is to move beyond estimates and build a detailed, data-driven financial plan. Resources like the structured e-courses at pvknowhow.com are designed to guide prospective investors through this complex but critical planning phase, helping them account for every variable before the first container is shipped.