An investor identifies New Zealand as an ideal location for a new solar module manufacturing facility, drawn by its stable economy, commitment to renewable energy, and excellent trade links.

But after a promising industrial site is located and initial plans are drafted, progress meets a significant hurdle: the Resource Management Act (RMA), a comprehensive and uniquely structured piece of legislation. For any entrepreneur planning a major industrial project in New Zealand, understanding this framework isn’t just a regulatory formality—it’s critical to project viability.

This guide offers a clear overview of the RMA—its structure, the consent process, and key considerations for establishing a solar manufacturing plant—to give business leaders a practical understanding of the regulatory landscape before committing significant investment.

Understanding the Resource Management Act (RMA)

Enacted in 1991, the Resource Management Act is New Zealand’s primary law governing the use of natural and physical resources such as land, air, and water. At its core, the Act promotes the ‘sustainable management’ of these resources. In business terms, this translates to balancing economic development with environmental protection, while ensuring the needs of future generations are not compromised.

Unlike the centralized regulatory bodies found in many countries, the RMA establishes a decentralized system. This is a crucial distinction for international investors, as project approval isn’t sought from a single national agency. Instead, authority is distributed across three tiers of government.

The Three Tiers of Environmental Governance

-

Central Government: Sets the overall direction through National Policy Statements (NPS) and National Environmental Standards (NES). For a solar manufacturing project, the National Policy Statement on Renewable Electricity Generation (NPS-REG) is particularly relevant, as it directs local authorities to accommodate renewable energy activities.

-

Regional Councils: These bodies are responsible for managing resources that cross district boundaries, including water catchments, air quality, and coastal environments. A solar factory requiring significant water or generating any air emissions would need to engage with the relevant regional council.

-

District and City Councils (Territorial Authorities): This level of governance most directly impacts site selection and factory development. District Plans, created by these councils, set out specific rules for land use in different zones (e.g., industrial, rural, commercial), covering regulations on building height, noise levels, traffic generation, and permissible activities.

This tiered structure means a single project may require approvals from both a regional council (for water permits or discharge consents) and a district council (for land use consent).

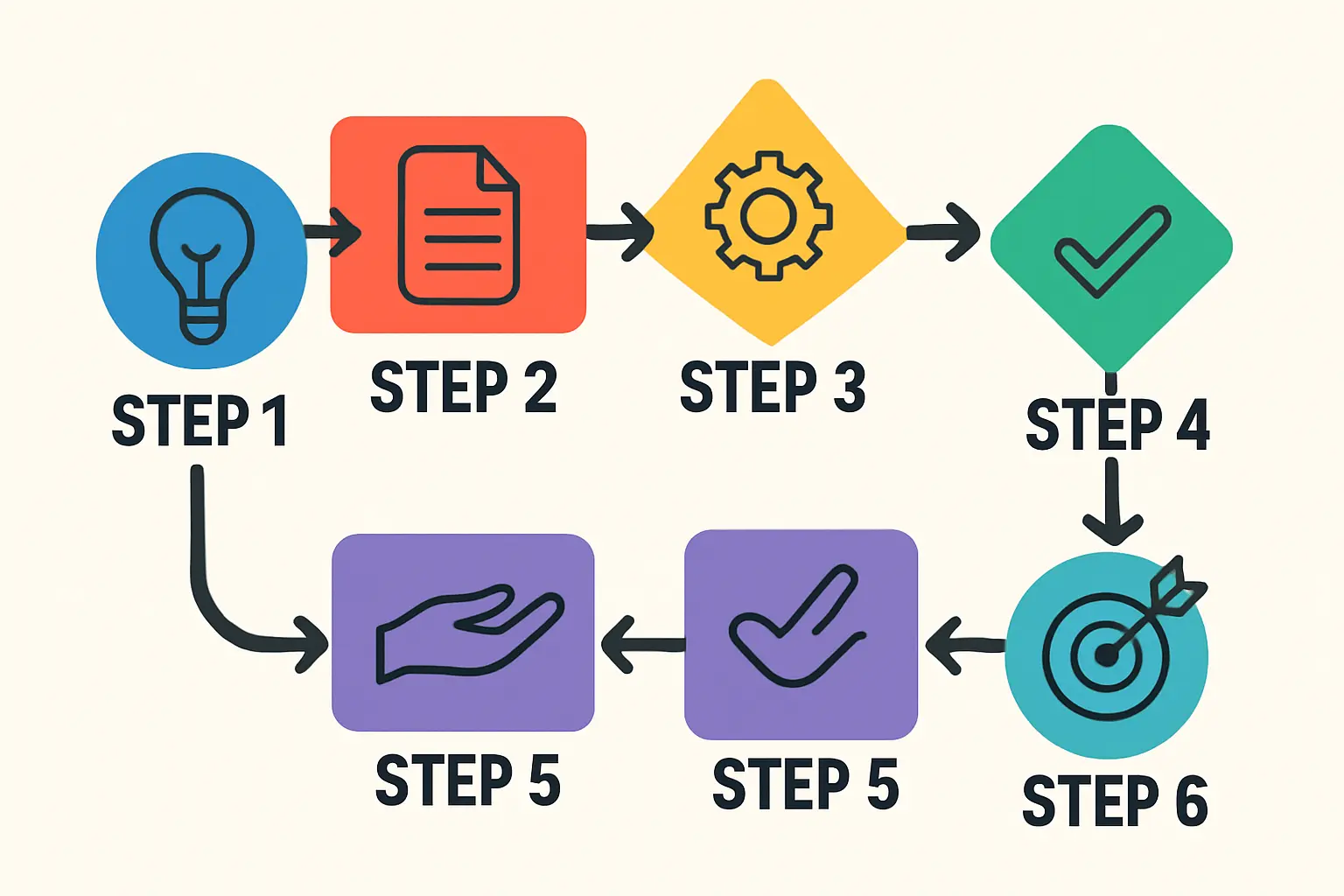

The Resource Consent Process: Gaining Official Approval

To establish and operate a solar factory, you must obtain a ‘resource consent.’ This formal approval is required for any activity not explicitly permitted as a right under the relevant district or regional plan. For an industrial facility, several types of consent are typically necessary.

Key Consent Types for a Solar Factory

Land Use Consent: This is the foundational requirement for a new manufacturing plant. It confirms that the activity is appropriate for the site’s zoning and complies with local land use rules. A clear factory layout and design is essential for this application, as it forms the basis for assessing the project’s impact.

Water Permits: If the manufacturing process requires taking water from a river, lake, or groundwater source, a specific permit is needed.

Discharge Permits: These are required to release any contaminants into the environment. This could include treated wastewater discharged into a waterway, emissions into the air from lamination or soldering, or contaminants to land.

The cornerstone of any resource consent application is the Assessment of Environmental Effects (AEE). This detailed report identifies all potential environmental impacts of the proposed factory—from construction noise and operational traffic to chemical storage and waste disposal—and outlines the measures planned to avoid, remedy, or mitigate them.

Specific Considerations for Solar Manufacturing Projects

While the RMA process applies to all industries, several aspects are particularly relevant for a solar module factory.

Zoning and Site Selection

The choice of land is critical. A site within an area zoned for ‘Industrial’ or ‘Heavy Industrial’ use will have a much smoother path to approval than one in a rural or commercial zone. The AEE must demonstrate that the factory’s operations are compatible with surrounding land uses.

Consultation and Engagement

The RMA places a strong emphasis on consultation. Early and open engagement with the local council, neighbouring landowners, and the wider community is strongly advised.

Crucially, project planners must engage with local iwi (Māori tribal groups), who are recognized as Tangata Whenua—the indigenous people of the land. Iwi have a statutorily recognized role in resource management as kaitiaki (guardians). Meaningful consultation is not only a matter of cultural respect but often a legal necessity that can preempt challenges that might otherwise delay a project for months.

The Evolving Regulatory Landscape: RMA Reforms

Investors should be aware that the Resource Management Act is undergoing significant reform. The government is replacing it with a new suite of laws, primarily the Natural and Built Environment Act (NBA) and the Spatial Planning Act (SPA).

Projects initiated during this transition period will need to navigate a framework incorporating elements of both the old and new systems. This complexity reinforces the need for expert local guidance, making an understanding of these evolving regulations a core part of the due diligence process for site selection.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

How long does the resource consent process typically take?

The timeline varies significantly with a project’s complexity and environmental effects. A straightforward application may be processed in three to six months, while a complex or publicly notified application can take over a year.

Does the pro-renewable energy policy (NPS-REG) guarantee approval?

No. While the NPS-REG creates a favourable policy environment for renewable energy projects like solar farms, a manufacturing facility is assessed primarily as an industrial activity. Although the facility’s benefits to the renewable sector are a positive factor, they do not override the need to meet all local environmental standards for an industrial plant.

What is the most common reason for delays or rejection?

Inadequate information in the Assessment of Environmental Effects (AEE) and insufficient consultation are common causes of delay. Failing to accurately identify and propose mitigation for all potential effects can lead to council requests for more information and, in some cases, public opposition.

Is it necessary to hire a local planning consultant in New Zealand?

While not mandatory, it is highly recommended. A local consultant brings an in-depth understanding of specific district and regional plans, established relationships with council staff, and experience navigating the nuances of the RMA, including the current reforms.

Your Next Steps in Planning

Navigating New Zealand’s Resource Management Act is a detailed but manageable process. For any international business professional, success lies in understanding its decentralized structure, preparing a thorough Assessment of Environmental Effects, and committing to genuine consultation with all stakeholders.

While rigorous, this regulatory framework provides a clear pathway for well-planned projects that align with New Zealand’s commitment to sustainable development. A thorough grasp of these requirements is a fundamental prerequisite before accurately calculating the initial investment for a solar factory. Structured educational resources, such as those provided by pvknowhow.com, can help investors build a foundational understanding before they engage local experts and begin this critical phase of their project.