An entrepreneur has a comprehensive business plan, secured funding, and identified a promising market for solar module production in Southeast Asia. Thailand, with its strategic location and growing economy, seems like an ideal base of operations.

However, the most critical—and often underestimated—challenges lie not in the business plan but in the ground itself: the laws governing land ownership and the intricate process of building and operating a factory.

For foreign investors, understanding this unique legal landscape is the crucial first step. Failing to navigate these regulations correctly can lead to significant delays, unforeseen costs, and even the complete halt of a project. This article outlines the primary hurdles and strategic pathways for establishing a manufacturing facility in Thailand, ensuring your venture is built on a solid legal foundation.

The Fundamental Challenge: Foreign Land Ownership in Thailand

The cornerstone of Thai property law is Section 96 of the Land Code Act, which generally prohibits foreign individuals or entities from owning land. While this may seem like a prohibitive barrier, the Thai government has established several well-defined legal pathways to facilitate foreign investment in its industrial sector. For a prospective solar module manufacturer, there are three primary options to consider.

Option 1: Long-Term Leasing

The most straightforward approach is to lease land. Thai law permits registered leases for a maximum of 30 years, which can often be structured with an option to renew for an additional period.

- Structure: A common arrangement is an initial 30-year lease with a pre-agreed contract for a second lease term, effectively providing control for several decades.

- Advantages: This method avoids the complexities of ownership and is relatively quick to implement.

- Limitations: The investor never holds title to the land, which can be a consideration for long-term capital investment and asset valuation.

Option 2: Thai Majority-Owned Company

Another route is to form a Thai limited company to purchase land. However, for the company to be considered ‘Thai,’ at least 51% of its shares must be held by Thai nationals.

- Structure: Foreign investors hold a 49% minority stake, relying on shareholder agreements to maintain operational control.

- Advantages: This structure allows the company to own land directly.

- Limitations: This path carries inherent risks related to control and requires a high degree of trust in local partners. For most industrial-scale projects requiring full foreign control, this is not the preferred solution.

Option 3: The Board of Investment (BOI) Pathway

For significant industrial projects like solar module manufacturing, the most strategic and secure route is often through promotion by the Thailand Board of Investment (BOI). The BOI is a government agency established to promote foreign investment in targeted industries that align with national development goals.

Obtaining BOI promotion is a game-changer, as it can grant a foreign-owned entity the privilege of owning land for its industrial operations.

Key Benefits of BOI Promotion:

- 100% Foreign Land Ownership: A BOI-promoted company can be granted the right to own the land necessary for its operations.

- Tax Incentives: These often include corporate income tax exemptions for up to eight years, along with waivers on import duties for machinery and raw materials.

- Work Permits: The BOI simplifies the process of obtaining visas and work permits for foreign specialists and management.

- Permission to Remit Funds: Streamlined processes for repatriating profits in foreign currency.

For those planning to start a solar factory, the BOI pathway is typically the most recommended approach, providing both legal security and significant financial incentives.

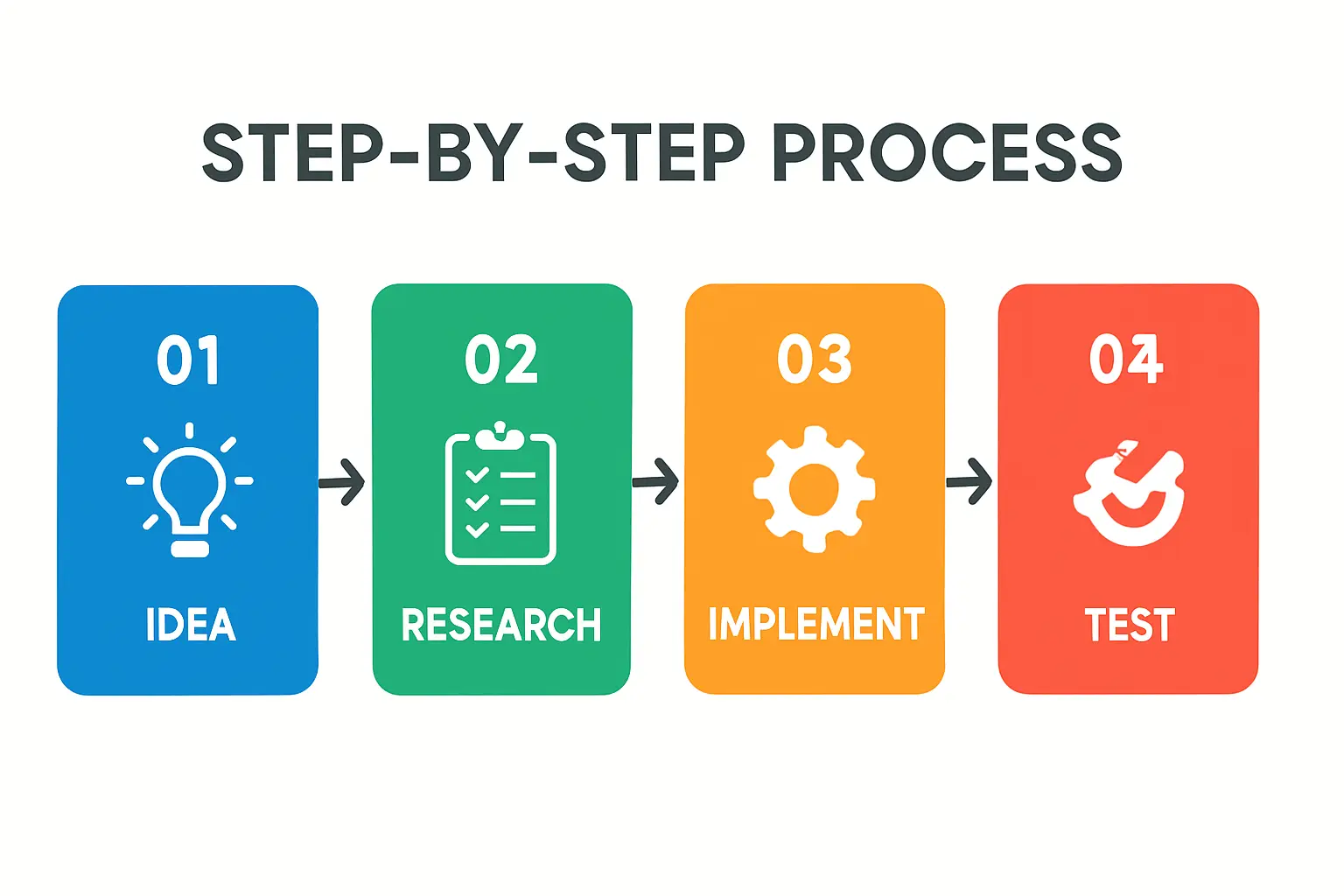

Securing the Necessary Permits: A Step-by-Step Overview

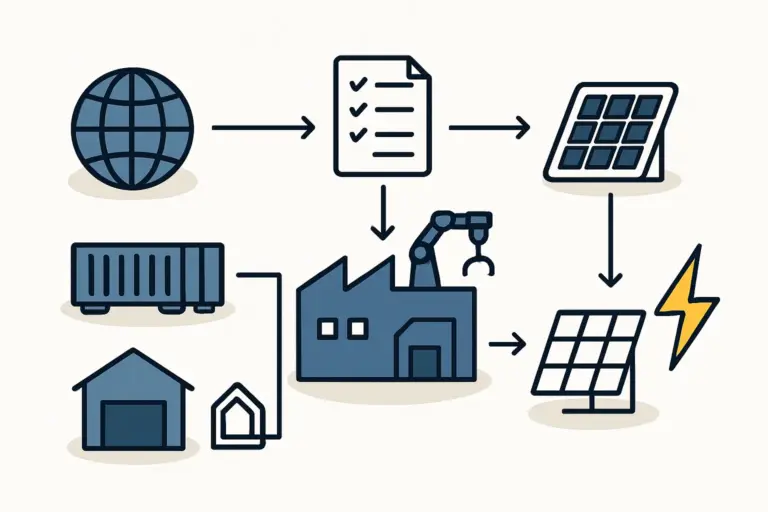

Acquiring land is only the beginning. Constructing and operating a factory in Thailand requires navigating a sequence of licenses and permits from various government bodies. This process demands meticulous documentation and a deep understanding of local administrative procedures.

Pre-Construction: Zoning and Environmental Clearances

Before any construction begins, the chosen site must comply with local zoning regulations. Locating the factory within a designated industrial estate often simplifies this process, as these areas are pre-zoned for industrial use and typically have the necessary infrastructure in place.

Depending on the scale and nature of the factory, an environmental assessment will be required. This could be an Initial Environmental Examination (IEE) for smaller projects or a more comprehensive Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) for larger ones. These reports must be approved before any construction permits are issued.

The Construction Permit (Or.1)

To begin building the factory, a Construction Permit (known as Or.1) must be obtained from the local municipal office (OrBorTor). This application requires detailed architectural and engineering plans that conform to Thai building codes and safety standards. The review process is thorough, and any non-compliance can lead to revision requests and delays.

The Factory License (Ror.Ngor.4)

Once the factory is constructed and machinery is installed, the final and most critical step is to obtain the Factory License (Ror.Ngor.4) from the Department of Industrial Works. This license grants permission to begin manufacturing operations.

The application process involves a final inspection of the facility to ensure that all machinery, safety systems, waste management protocols, and operational procedures comply with the Factory Act. The specifications of a turnkey solar manufacturing line must align with these local requirements—a detail an experienced implementation partner will manage.

A Realistic Timeline and the Value of Local Expertise

Navigating the full sequence of land acquisition, BOI application, and factory permitting is a complex undertaking. A realistic timeline, from initial planning to the start of operations, is typically 6 to 12 months, assuming no major setbacks.