Entrepreneurs often focus intensely on the initial capital required to launch a new venture. Securing funds for machinery and a facility can feel like the final hurdle, but for a solar module factory, this is only the beginning.

The long-term profitability and sustainability of the operation depend not on initial setup costs, but on the ongoing operational expenditures (OpEx) that begin the moment production starts.

Accurately forecasting these recurring costs separates a viable business from a project that struggles with cash flow. This article provides a reference financial model, using Uruguay as a case study, to illustrate the key operational costs an investor must anticipate for a 50 MW solar module factory. While the figures are specific, the underlying principles apply globally.

The Core Components of Operational Expenditure (OpEx)

Before we dive into the numbers, it’s essential to distinguish between the two primary types of expenses.

Capital Expenditure (CapEx): This is the one-time initial investment in long-term assets, such as machinery, equipment, and building construction.

Operational Expenditure (OpEx): These are the recurring costs required for the day-to-day running of the factory.

The primary OpEx categories for a solar module factory include direct labor, electricity, raw material logistics, and administrative overhead. Miscalculating any of these can significantly impact financial projections and the long-term health of the business.

A Reference Model: 50 MW Factory in Uruguay

To put these concepts into practice, we will model a hypothetical 50 MW factory operating on a single daily shift—a common entry point for new manufacturers in emerging markets. The following breakdown uses current data from Uruguay to provide a realistic, though illustrative, financial picture.

This model is built on four pillars of operational cost: labor, electricity, logistics, and administration.

Deconstructing Labor Costs in Uruguay

Direct labor is one of the most significant and frequently underestimated operational costs. The advertised salary is only a fraction of the total expense to the employer, particularly in countries with robust social security systems like Uruguay.

Base Salaries and Skill Levels

A 50 MW production line typically requires a staff of 25 to 30 people, including:

- Production Operators: Responsible for machine operation and manual assembly.

- Technicians: For machine maintenance, quality control, and process supervision.

- Engineers and Management: To oversee production, logistics, and overall plant operations.

In Uruguay, monthly base salaries for these roles can range from approximately $800 USD for an entry-level operator to over $2,500 USD for a skilled engineer or supervisor.

Mandatory Social Contributions (The ‘On-Cost’)

This is where many financial models fall short. An employer’s cost extends far beyond the employee’s net pay. In Uruguay, mandatory contributions add a substantial percentage on top of the base salary.

- Social Security (BPS): A significant contribution covering retirement, family allowances, and unemployment benefits.

- National Health Insurance (FONASA): A mandatory contribution to the public healthcare system.

- Workplace Accident Insurance (BSE): Compulsory insurance covering accidents and occupational illnesses.

Combined, these contributions typically add around 25-30% to the base salary cost for the employer.

Annual Bonuses and Other Provisions

Uruguayan law mandates an annual bonus known as ‘Aguinaldo,’ which is equivalent to a 13th-month salary paid in two installments. When this and other provisions like paid leave are factored in, the total employer cost can be up to 1.6 times an employee’s base salary.

Example Calculation: For an employee with a base salary of $1,000 USD, the actual annual cost to the company could be closer to $1,600 USD per month after all contributions and provisions are included. This ‘on-cost’ is a critical factor for accurate financial forecasting.

Analyzing Industrial Electricity Tariffs

After labor, electricity is a major OpEx driver, directly linked to the manufacturing process. Uruguay’s state-owned utility, UTE, has a transparent but complex tariff structure for industrial users that presents both a challenge and an opportunity.

Understanding Uruguay’s UTE Tariff Structure

Industrial electricity is not priced at a flat rate. The cost varies significantly depending on the time of day, a system designed to manage grid load.

- Punta (Peak): The most expensive period, typically during evening hours (e.g., 6 PM – 10 PM).

- Llano (Shoulder): A mid-priced period covering most of the business day.

- Valle (Off-Peak): The cheapest period, usually overnight and on weekends.

Calculating the Monthly Bill

An industrial electricity bill has three main components:

- Fixed Charge: A standard monthly fee for being connected to the grid.

- Power Charge (Potencia Contratada): A charge based on the maximum power demand contracted by the factory, with different rates for the Punta, Llano, and Valle periods.

- Energy Charge (Energía): The charge for the actual kilowatt-hours (kWh) consumed, again priced differently for each time-of-use period.

Strategic Opportunity for Cost Reduction

This tariff structure offers a clear path to cost optimization. By scheduling the single production shift to operate primarily within the Llano and Valle periods—and avoiding the expensive Punta hours—a factory can reduce its monthly electricity costs by 20-30% or more. This strategic decision, made during the planning phase, has a direct and lasting impact on profitability.

Logistics: The Cost of Importing Raw Materials

As an assembly operation, a solar module factory relies on a steady flow of imported materials like solar cells, glass, EVA encapsulant, and backsheets. The majority of these will arrive by sea, making the Port of Montevideo the primary entry point.

Port and Customs Fees

The cost of getting a container from the ship to the factory gate involves several fees:

- Terminal Handling Charges (THC): Levied by the port operator for handling the container.

- Security & Scanning Fees: Standard port security charges.

- Customs Brokerage: The fee for a licensed broker to clear goods through customs.

For a standard 40-foot container, these costs can amount to several hundred dollars. A 50 MW factory may require 15-20 such containers per month.

Inland Transportation

Once cleared, the container must be transported to the factory by truck. In Uruguay, this cost is typically calculated per kilometer. A factory located 100 km from the port will have a significantly lower logistics cost than one 400 km away, underscoring the importance of strategic site selection.

Administrative and Overhead Costs (SG&A)

The final category, Sales, General & Administrative (SG&A) expenses, covers all non-production costs. This includes:

- Salaries for management, sales, and administrative staff.

- Office rent and utilities.

- Marketing and sales expenses.

- Legal and accounting services.

- Contingency funds.

As a general benchmark for financial modeling, SG&A costs often represent 5% to 8% of a company’s annual revenue.

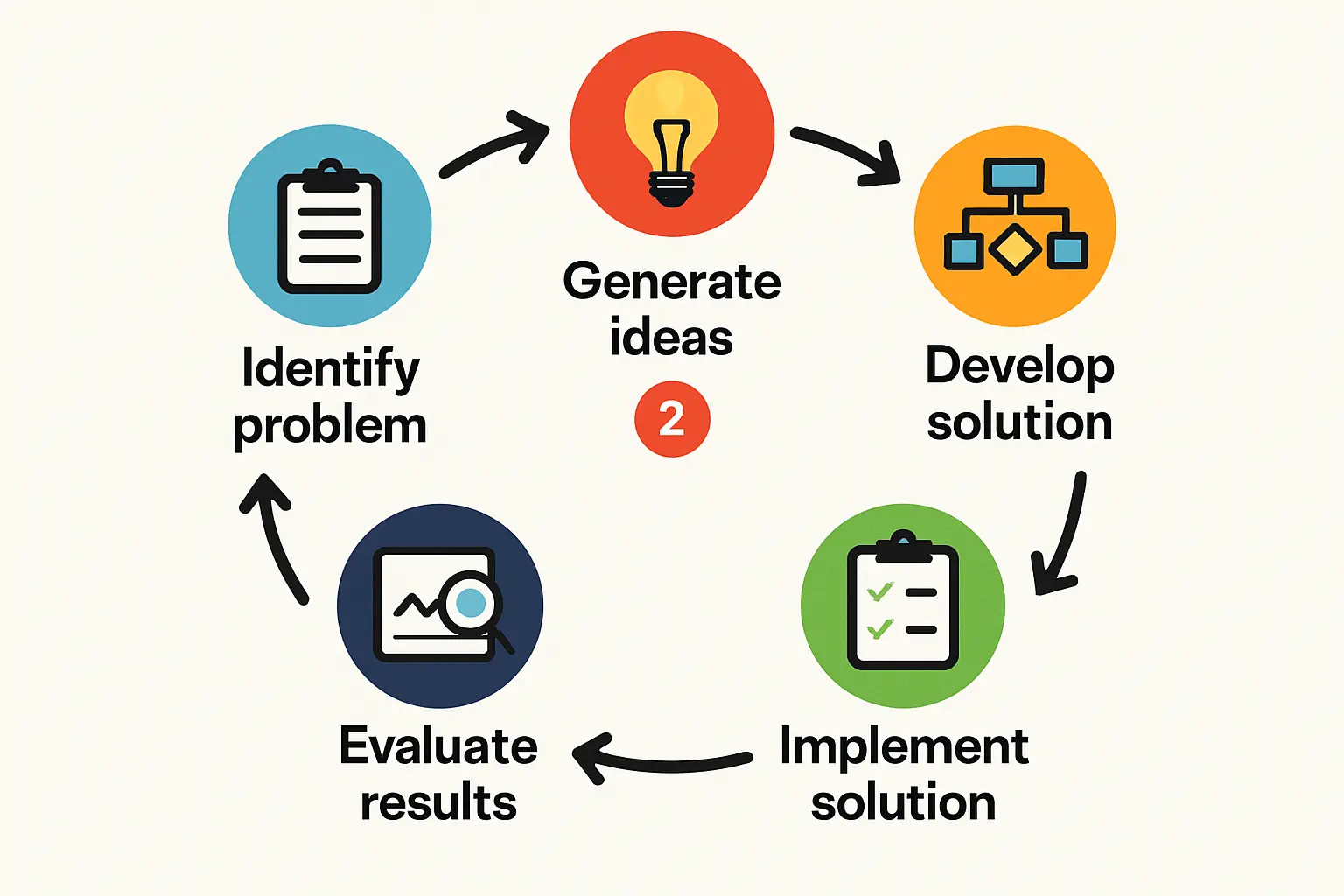

Integrating Costs into a Financial Projection

By methodically estimating these four key OpEx categories, an entrepreneur can build a robust financial model. Such a detailed forecast is an essential part of a comprehensive business plan and is critical for determining the factory’s break-even point, pricing strategy, and overall profitability.

A well-researched financial plan can also help investors leverage national programs like Uruguay’s Investment Promotion Law (Law 16.906), which offers significant tax incentives for projects declared to be of national interest.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: Why use Uruguay as an example for this financial model?

Uruguay was selected for its stable economy, transparent legal and tax frameworks, and well-documented utility and labor cost structures. Its position as a logistics hub in South America also makes it a representative case study for estimating costs in an emerging market.

Q2: How do these OpEx figures relate to the initial investment in the factory?

OpEx represents the ongoing costs to operate the factory after the initial investment (CapEx) in machinery and the building has been made. A complete financial analysis requires a clear understanding of both, as CapEx determines the entry cost while OpEx dictates long-term profitability.

Q3: Can a solar module factory be profitable with these operational costs?

Absolutely. Profitability is a function of managing costs, optimizing production efficiency, securing competitive raw material prices, and executing a strong sales strategy. Accurate OpEx modeling is the foundational step to ensure the business is structured for success from day one.

Q4: How does pvknowhow.com assist with this type of analysis?

J.v.G. Technology has been developing turnkey factory concepts since the 1990s. This experience is the foundation of the pvknowhow.com platform, which provides structured e-courses, business plan templates, and direct consultancy to help entrepreneurs create precise financial models tailored to their specific location and business goals.

Ultimately, a deep understanding of operational expenditures transforms a business idea into a bankable project. While securing initial capital is a major milestone, mastering ongoing costs is what builds a resilient and profitable manufacturing enterprise for the long term. The methodology of breaking down labor, energy, logistics, and administrative costs is a universal tool for success, whether in Uruguay or any other market worldwide.