An international entrepreneur looking at Canada’s burgeoning clean energy market sees immense potential, noting the stable political environment, government incentives, and high demand for renewable energy. Yet they may overlook the single most critical factor for long-term success: the central role of First Nations, Métis, and Inuit communities. In Canada, building a major industrial project is no longer just about securing land and capital; it is about building trust and creating shared value with Indigenous partners.

This shift, known as economic reconciliation, is more than a social objective—it is a powerful business strategy. With the Indigenous economy projected to grow from $32 billion to $100 billion by 2025 and more than 60,000 Indigenous-owned businesses in operation, partnership is the gateway to a dynamic and expanding economic force. For any professional planning to enter the Canadian solar manufacturing sector, success hinges on the ability to build genuine, respectful, and mutually beneficial partnerships. This article provides a framework for doing just that.

Table of Contents

Understanding the Foundation: Why Indigenous Partnership is Non-Negotiable

For decades, industrial development in Canada involved minimal “consultation” with Indigenous communities—a process often treated as little more than a final checkbox on a regulatory application. That model is obsolete. The legal, political, and economic landscape has fundamentally changed, driven by landmark court rulings and the federal government’s adoption of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP).

Today, the concept of “Free, Prior, and Informed Consent” (FPIC) serves as the guiding principle. While the legal “Duty to Consult” officially rests with the government (the Crown), the most successful companies recognize that proactive and direct engagement is indispensable. Projects that move beyond mere consultation to form true equity partnerships with Indigenous communities gain a powerful advocate. This social license to operate translates into tangible business advantages, including greater project certainty, fewer delays, and a more stable investment environment.

The economic case is just as compelling. A partnership is not a concession; it is an alliance with a sophisticated and rapidly growing economic force. Indigenous corporations and economic development groups are actively seeking investment opportunities that align with their values, particularly in sustainable sectors like clean energy. By forming a joint venture, a solar manufacturing entrepreneur gains access to local knowledge, a dedicated workforce, and unique funding opportunities that would otherwise be unavailable.

Models for Structuring Joint Ventures and Equity Partnerships

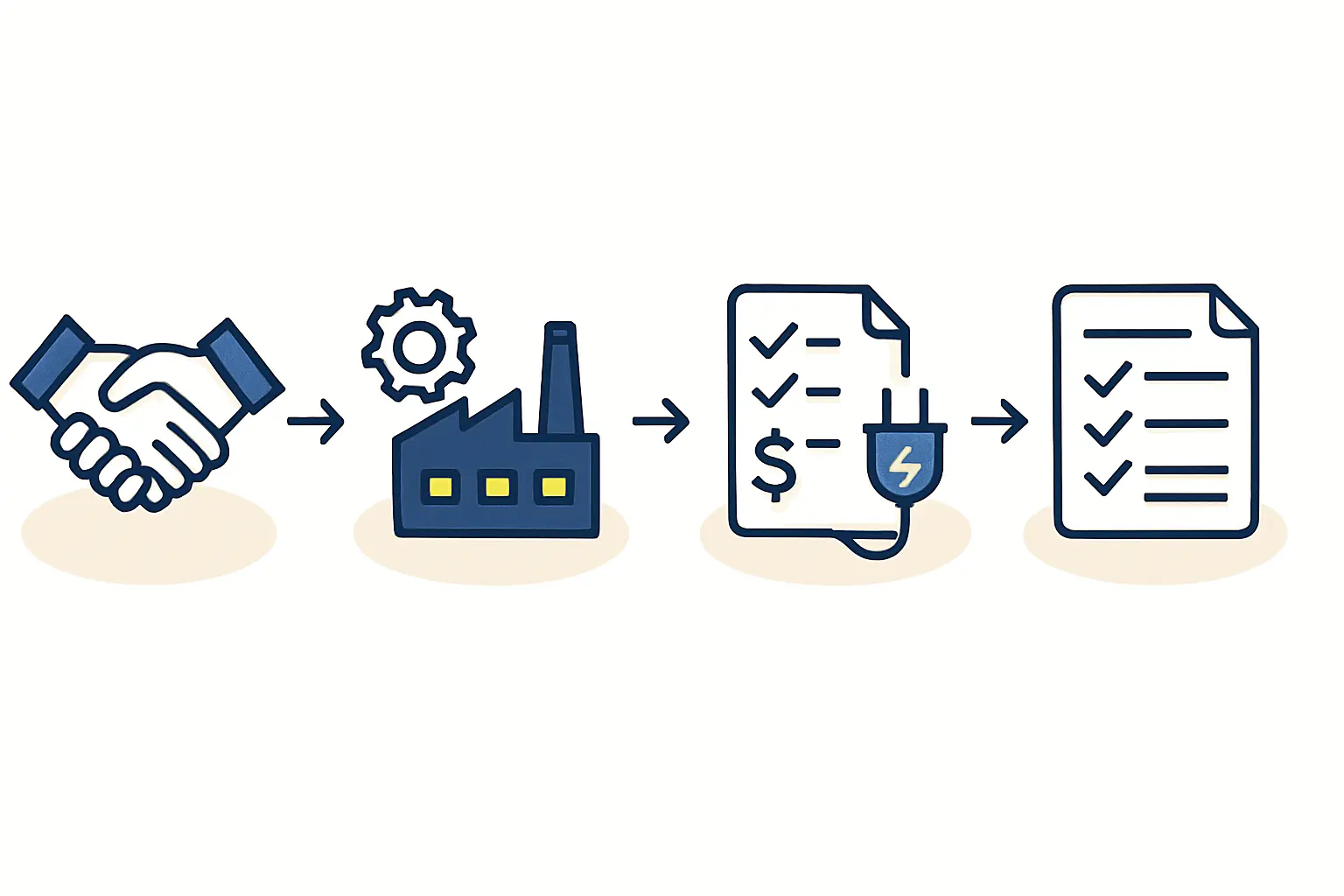

For a partnership to succeed, its structure must align the interests of all parties. While every agreement is unique, three common models provide a starting point for discussion and can be adapted or combined to suit the specific goals of the business and the community partner.

1. Equity Partnerships

In this model, the Indigenous community holds a direct ownership stake in the solar module manufacturing facility. This is the most integrated form of partnership and one that is increasingly becoming the standard for major projects in Canada.

Business Logic: When both parties are equity holders, their long-term interests are aligned. Shared success fosters a deep commitment to the project’s operational efficiency and profitability. This model is also highly favoured by federal funding bodies, as it demonstrates a genuine commitment to economic reconciliation.

2. Limited Partnerships (LPs)

A Limited Partnership allows an Indigenous community’s economic development corporation to invest as a limited partner. The community provides capital, land, or other assets for a share of the profits, while the general partner (the entrepreneur or their company) retains control over daily operations.

Business Logic: This structure offers a clear separation of roles, which can be a key advantage if the community partner lacks prior experience in industrial manufacturing. It allows them to benefit financially from the venture while relying on the operational expertise of their business partner.

3. Impact and Benefit Agreements (IBAs)

IBAs are contractual agreements outlining the specific, tangible benefits a project will deliver to the community. These often include employment targets, skills training programs, local procurement commitments, and direct investment in community infrastructure like schools or health centres.

Business Logic: While sometimes used as standalone agreements, IBAs are most effective when they complement an equity or limited partnership. They formalize the project’s social commitments in measurable, accountable terms, ensuring the venture contributes to the community’s well-being beyond simple profit-sharing.

Navigating the Funding and Support Ecosystem

One of the greatest advantages of partnering with an Indigenous community is access to dedicated funding streams and financial incentives designed to support co-developed projects. These programs can substantially improve a project’s financial viability.

Federal and Institutional Support

Canada Infrastructure Bank (CIB): Through its Indigenous Community Infrastructure Initiative, the CIB has a target to invest at least $1 billion in projects that benefit Indigenous peoples. The bank provides low-cost, long-term debt financing—often a crucial element for capital-intensive projects like a manufacturing plant.

Indigenous Services Canada (ISC): ISC offers various programs, such as the Community Opportunity Readiness Program (CORP), which provides non-repayable contributions for the pre-development phase. This funding can cover essential feasibility studies, business planning, and engineering designs, helping to de-risk the project for private investors.

Tax Incentives and Credits

Clean Technology Manufacturing Investment Tax Credit: The Canadian government offers a 30% refundable tax credit for investments in machinery and equipment used to manufacture renewable energy components, including solar panels. While available to all, projects with strong Indigenous partnerships are often viewed more favourably within the broader policy framework, which can smooth the path for approvals and support.

A Practical Framework: Key Steps to Building Trust and Success

The process of forming a partnership is as important as the final legal agreement. It requires patience, transparency, and a genuine commitment to building a relationship based on mutual respect.

Step 1: Early and Respectful Engagement

The first conversation should happen before any significant plans are made. The goal is to introduce an idea, not to present a finished project for approval. It is vital to understand the community’s governance structure—whether decisions are made by an elected Chief and Council, hereditary leaders, or a community consensus process—and to follow their established protocols.

Step 2: Building Capacity and Shared Understanding

An entrepreneur brings technical knowledge of solar manufacturing; the community partner brings deep knowledge of the land, the local workforce, and the cultural context. Investing time to share this knowledge is crucial for a successful partnership. This might involve workshops on key production steps in a solar factory or sessions where community elders share the cultural significance of the proposed site. Experienced external advisors can often help facilitate these technical discussions, ensuring they are neutral and accessible.

Step 3: Ensuring Long-Term Community Benefits

Discussions must extend beyond financial returns. The most durable partnerships are those that create lasting value for the community. This includes developing skills training programs with local colleges, establishing clear career pathways for community members within the factory, and creating apprenticeship opportunities for youth.

Step 4: Formalizing the Partnership with Patience

Building trust takes time. The process of negotiating a formal agreement should not be rushed. Many Indigenous communities operate on a timeline guided by consensus-building, which can be more deliberate than a typical corporate schedule. The legal documents should be the final step that formalizes a relationship already built on trust, not the tool used to create it.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: What is the ‘Duty to Consult’?

A: The ‘Duty to Consult’ is a legal obligation on the part of the Crown (federal and provincial governments) to consult with Indigenous peoples when a proposed action might impact their established or potential Aboriginal rights. The most successful companies do not wait for the government; they engage directly with communities as partners, going far beyond this legal minimum.

Q: How long does it take to form a partnership?

A: There is no set timeline. The process is relationship-driven and moves at the speed of trust. It can range from six months to two years, depending on the complexity of the project and the community’s decision-making processes.

Q: What if a community has no experience in manufacturing?

A: This is an opportunity, not a barrier. The business partner brings the technical and operational expertise. The community partner brings other critical assets: land, a potential workforce, local knowledge, political support, and access to specific funding programs. The venture’s success depends on combining these complementary strengths.

Q: Are these partnerships only for large-scale projects?

A: No. The principles of respect, co-creation, and shared benefit apply to projects of any size. The structure of the partnership may be simpler for a smaller facility, but the importance of the relationship remains the same.

Q: Is this framework unique to Canada?

A: While forming partnerships with local communities is a global best practice, the Canadian context is unique, shaped by the country’s specific history, constitutional law recognizing Aboriginal rights, and the national commitment to reconciliation with First Nations, Métis, and Inuit peoples.

Conclusion: Partnership as a Competitive Advantage

For any professional looking to establish a solar manufacturing presence in Canada, viewing Indigenous partnership as a regulatory hurdle is a critical mistake. It should instead be seen as the country’s single greatest competitive advantage.

A project co-developed with an Indigenous partner is more resilient, better financed, and far more likely to receive regulatory and community support. It ceases to be a foreign investment and becomes part of the local economic fabric. By embracing a framework of early engagement, shared ownership, and mutual respect, an entrepreneur can build a business that is not only profitable but also contributes meaningfully to the powerful movement of economic reconciliation in Canada.