Disclaimer: This case study represents a composite example derived from real-world

consulting work by J.v.G. Technology GmbH in solar module production and factory optimization. All data points are realistic but simplified for clarity and educational purposes.

A major mining operation is established in a remote region of Niger, hundreds of kilometers from the nearest reliable power grid. Its success hinges on a constant energy supply, but its greatest operational vulnerability is the very source of that power: diesel fuel. The logistical chain is long, expensive, and subject to disruption, making energy both a significant cost center and a point of constant risk.

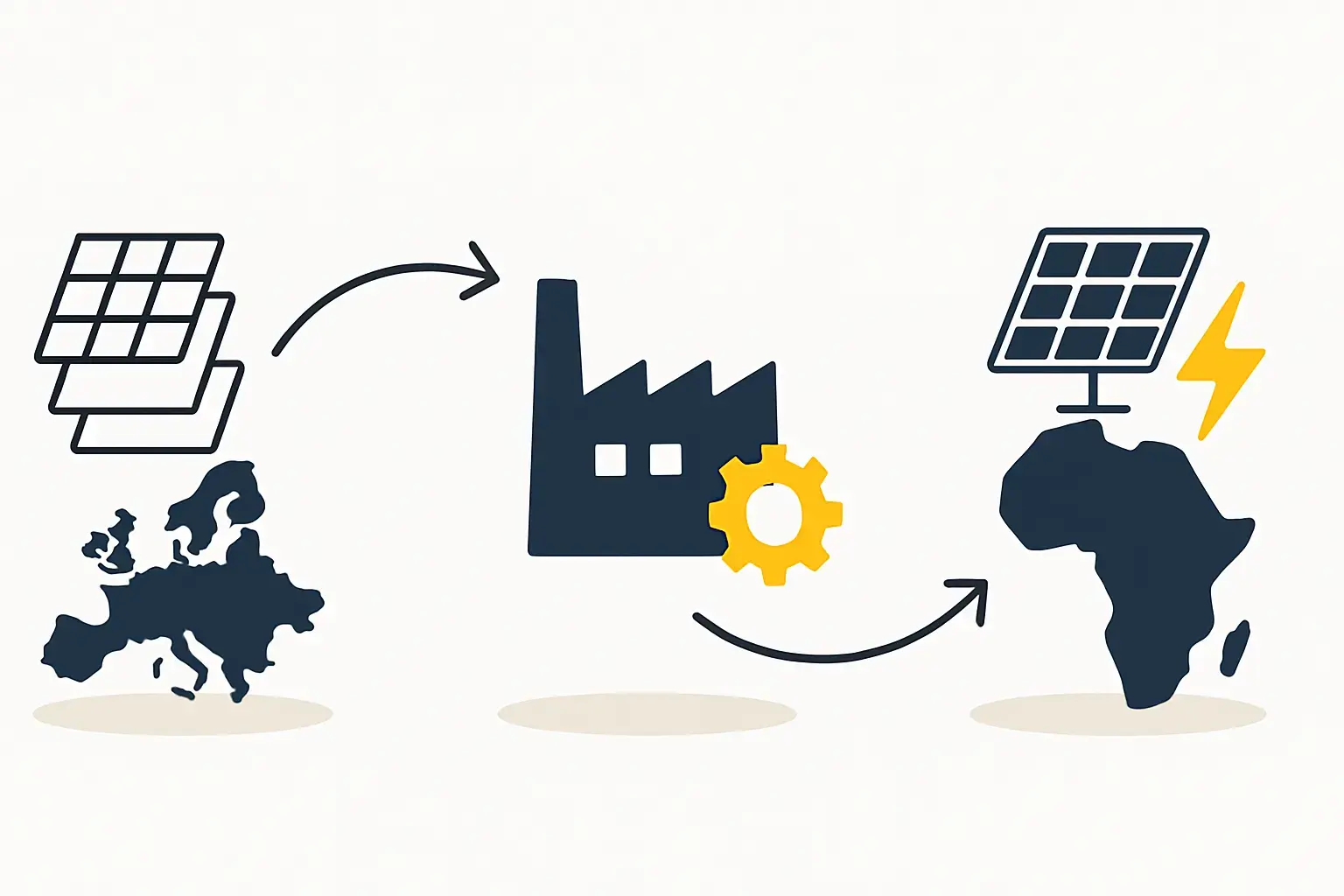

This scenario is common across the Sahel. A different operational model, however, offers a strategic solution. Instead of transporting fuel or fragile finished solar panels across difficult terrain, what if the solar modules themselves were assembled directly on-site? This article outlines the operational plan for a mobile, containerized solar module assembly line—a concept that can transform a logistical challenge into a powerful asset for remote industrial development.

The Sahel’s Industrial Challenge: A Convergence of Need and Opportunity

The Sahel region is rich in mineral resources—including gold, uranium, and phosphates—attracting significant investment in mining and large-scale infrastructure. Yet, these operations face a fundamental obstacle: a profound energy deficit. According to the World Bank, grid electricity access in many Sahelian countries remains below 50% even in urban areas and is virtually nonexistent in the remote locations where most industrial projects are sited.

This forces a reliance on diesel generators, which creates several critical business challenges:

- High Operational Costs: Fuel must be transported over vast distances, incurring substantial costs and logistical complexity.

- Supply Chain Vulnerability: Dependence on fuel deliveries creates a single point of failure that can halt operations worth millions of dollars per day.

- Environmental and Regulatory Pressure: A growing global focus on sustainability places diesel-powered operations under scrutiny.

Localized solar power is the logical alternative, especially since the Sahel boasts some of the highest solar irradiation levels in the world. The challenge is not the resource itself, but the logistics of building a multi-megawatt solar farm in a location with limited infrastructure.

The Mobile Factory Concept: A Paradigm Shift in Remote Power Generation

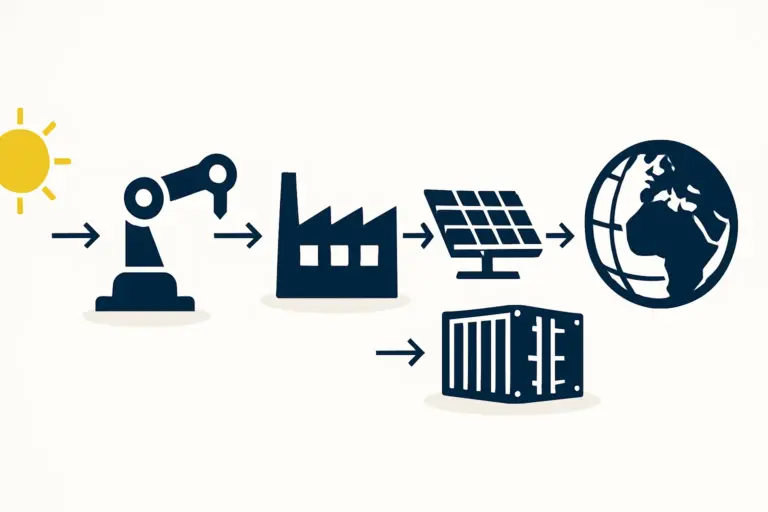

A mobile, containerized solar module factory is not a facility for manufacturing solar cells from raw silicon. It is, instead, a sophisticated assembly line housed within standard shipping containers and designed for on-site deployment.

The core of the model is assembling modules from prefabricated kits. Essential components—solar cells, glass, backsheets, and frames—are packed and shipped efficiently as a “Bill of Materials” (BOM). Once on-site, these components are fed into the containerized line to produce finished, quality-tested solar modules. This approach fundamentally alters the logistics of remote solar farm construction. Planning such an operation requires a deep understanding of the solar module manufacturing process.

A Phased Operational Plan for Deployment

Executing this project requires a structured approach, which can be broken down into four distinct phases based on experience gained from European PV manufacturers’ turnkey projects.

Phase 1: Strategic Partnership and Feasibility

This model is rarely a standalone venture. Its success typically hinges on a partnership with a major Engineering, Procurement, and Construction (EPC) company or the industrial entity itself (e.g., a mining corporation) that requires the power.

The initial phase involves a rigorous feasibility study to assess:

- Site Power Requirements: Determining the target size of the solar farm (e.g., 10 MW, 50 MW) to meet the industrial project’s energy needs.

- Logistical Analysis: Mapping transport routes from the nearest port to the final site, identifying potential bottlenecks, and planning for security.

- Site Preparation: Allocating a level, secure area for the container line and for storing raw materials and finished modules.

- Commercial Viability: Modeling the total cost, including the investment to start a solar panel factory equipment, against the long-term savings from reduced diesel consumption.

Phase 2: Logistics and Supply Chain for Module Kits

This is the logistical heart of the operation. Instead of shipping bulky, fragile glass modules, the project transports compact, durable raw material kits, often in a Semi-Knocked Down (SKD) or Completely Knocked Down (CKD) format.

This strategy offers a significant advantage in volume efficiency. The components required to produce several containers’ worth of finished modules can often be shipped in a single container, which drastically reduces transportation costs and minimizes the risk of product damage over rough, unpaved roads—a frequent concern for project managers in the region. Managing the supply chain for this Bill of Materials thus becomes the primary logistical task.

Phase 3: On-Site Setup and Commissioning

Upon arrival, the containers are positioned on a pre-prepared concrete foundation. The setup process includes connecting the containers, establishing power and utility hookups, and commissioning the machinery.

This stage is typically overseen by a small, specialized team, often including an engineer from the equipment supplier to ensure every machine is calibrated correctly. Speed is a key business metric; a well-planned setup can have the line operational within two to four weeks of the containers arriving on-site, a critical timeline for capital-intensive industrial projects.

Phase 4: Assembly Operations and Quality Control

Once commissioned, the line begins assembly. A key benefit of this model is the opportunity to train and employ a local workforce. A typical semi-automated container line producing 50-100 modules per shift can be operated by a team of 10 to 15 local staff supervised by a trained production manager. This creates valuable local employment and facilitates skills transfer.

Quality control is non-negotiable. The harsh Sahelian climate, with its high ambient temperatures and abrasive dust, demands robust, high-quality modules. Each containerized factory must therefore be equipped with essential testing equipment, such as a sun simulator, to verify that every module produced on-site meets international performance and durability standards before it is installed in the field.

Key Advantages of the On-Site Assembly Model

Adopting this strategy offers several compelling advantages over the traditional approach of importing finished solar panels.

- De-risking Logistics: It solves the “last mile” problem by eliminating the transport of fragile finished products over challenging terrain, reducing breakage rates from as high as 5–10% to near zero.

- Cost Reduction: The higher density of shipping raw material kits significantly lowers freight costs per module. Furthermore, importing components rather than finished goods can, in some jurisdictions, lead to lower import duties.

- Speed and Flexibility: Modules are produced on-demand, feeding directly into the solar farm construction schedule. This avoids delays from international shipping and port congestion, allowing the EPC to control the timeline.

- Local Content and Job Creation: For projects involving state-affiliated entities or international development funding, the ability to demonstrate local job creation and skills development is a powerful strategic and political advantage. The model is uniquely suited for regions with high solar irradiation but weak grid infrastructure, aligning perfectly with national development goals.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What is the typical investment for such a mobile factory?

The investment depends on the level of automation and production capacity. A semi-automated line with a capacity of 20–50 MW per year represents a different capital outlay than a fully automated one. The pvknowhow.com platform provides resources to help develop a detailed business plan for such scenarios.

How many people are needed to run it?

A typical semi-automated line requires approximately 10–15 operators per shift for tasks like loading materials, supervising machine processes, and moving finished modules. An additional small team for quality control and maintenance is also necessary.

Do you need highly skilled engineers on-site permanently?

No. After the initial commissioning and training period, which is supervised by an expert engineer, day-to-day operations can be managed by a locally trained production supervisor and technicians.

What about dust and heat inside the containers?

The containers are environmentally controlled. They are equipped with industrial-grade HVAC (Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning) and air filtration systems to maintain a clean, temperature-stable environment suitable for high-precision electronics assembly.

How does this compare to just shipping finished modules?

While seemingly simpler, shipping finished modules to remote locations carries high costs for transportation and insurance, along with a significant risk of damage. The on-site assembly model shifts the complexity from fragile logistics to manageable on-site production, offering greater control, lower risk, and substantial cost savings on large-scale projects.

Conclusion: From Logistical Burden to Strategic Asset

For large-scale industrial projects in remote regions like the Sahel, energy is a foundational requirement. The mobile, containerized solar module factory reframes the challenge of remote power generation, shifting the paradigm from importing a fragile, finished product to implementing a robust, on-site manufacturing process.

This approach transforms a primary logistical burden into a strategic asset, delivering cost control, supply chain security, and operational flexibility. For entrepreneurs and corporations looking to power the next wave of industrial development in challenging environments, this operational blueprint offers a viable and compelling path forward. Navigating the technical and commercial complexities of such a venture requires specialized knowledge, and educational resources like those at pvknowhow.com are designed to guide decision-makers through every stage of the process.

Download the Sahel Remote Industrial Solar Case Study [PDF]

Author: This case study was prepared by the

turnkey solar module production specialists at J.V.G. Technology GmbH

It is based on real data and consulting experience from J.v.G. projects

worldwide, including installations ranging from 20 MW to 500 MW capacity.