A modern manufacturing facility can meet every building code, withstand a significant earthquake, and still be forced into bankruptcy. This outcome reveals a critical distinction for any industrial investor in Japan: the difference between structural survival and operational continuity.

While a building may remain standing, damaged equipment, broken supply lines, and a halted production floor can lead to catastrophic financial losses. For entrepreneurs entering the solar module manufacturing sector in a seismically active region like Japan, business continuity planning is as vital as the factory’s engineering. This article outlines the core principles of seismic design and risk mitigation, extending beyond basic compliance to ensure a new enterprise is not just safe, but truly resilient.

Beyond Survival: Why Standard Building Codes Are Just the Starting Point

Japan’s location on the Pacific ‘Ring of Fire’ means that over 1,500 seismic events are recorded annually, making it a global leader in earthquake engineering. The nation’s Building Standard Law (BSL) is one of the most rigorous in the world and has undergone major revisions, notably in 1981 and 2000, to enhance its structural integrity requirements.

The law distinguishes between two levels of seismic performance:

- Shiken: Resistance to moderate, more frequent earthquakes with minimal damage.

- Taishin: Advanced resistance to prevent collapse during severe, infrequent earthquakes.

However, the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake proved to be a crucial lesson for the industrial sector. Many buildings that were fully compliant with the Taishin standard did not collapse, yet they suffered extensive non-structural damage. Ceilings fell, internal pipelines ruptured, and heavy machinery shifted, rendering entire facilities inoperable for months. This widespread business interruption made it clear that legal compliance is merely the foundation; true resilience requires a more comprehensive approach.

Protecting Your Core Asset: The Manufacturing Line

In solar module manufacturing, the most valuable assets are inside the building. The precision machinery—from cell stringers to laminators and testers—is the heart of the operation. Protecting this equipment from both direct damage and misalignment is critical to business continuity. The focus, therefore, must shift to non-structural components, which are often the first to fail during an earthquake.

Seismic Design Philosophies for Factory Infrastructure

Modern engineering offers sophisticated solutions to protect not just the building shell but its contents and operations. The two primary approaches are base isolation and damping systems.

A base-isolated structure rests on flexible bearings or sliders that allow the ground to move underneath it during an earthquake, significantly reducing the shaking forces transferred to the structure and its contents. This is a critical factor in the initial design of a solar factory layout, as it fundamentally changes the foundation requirements.

Damping systems, analogous to shock absorbers in a vehicle, are devices integrated into the structure to absorb and dissipate seismic energy. Both methods aim to minimize building acceleration, which is the primary cause of damage to internal equipment and infrastructure.

Anchoring and Bracing Your Equipment

Even with an advanced structural system, the direct anchoring of machinery is essential. Each piece of solar module manufacturing equipment has a unique center of gravity, vibration sensitivity, and set of utility connection points, such as for electricity and compressed air. A seismic engineering plan involves:

- Secure Anchoring: Bolting machinery to a reinforced concrete floor using calculations that account for potential seismic loads.

- Flexible Utility Connections: Using flexible joints and pipes for electrical conduits, water, and gas lines to prevent them from shearing off during building movement.

- Bracing Tall or Slender Equipment: Ensuring that tall storage racks or automated transfer systems are braced against lateral movement to prevent tipping.

Such detailed planning is crucial for establishing a reliable, high-yield production environment from the start.

Business Continuity Planning: A Framework for Resilience

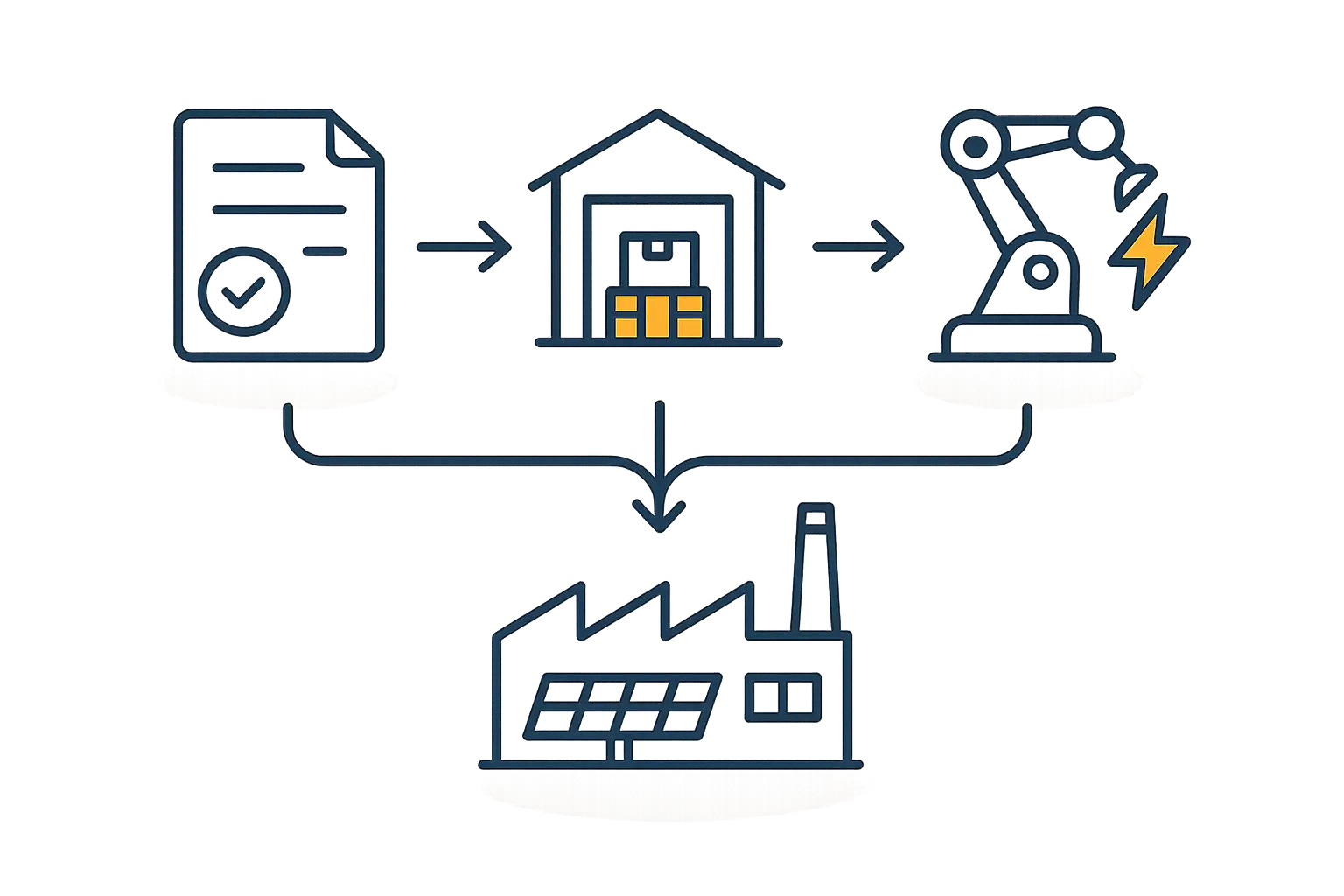

Seismic engineering is just one pillar of a broader Business Continuity Management System (BCMS), as defined by international standards like ISO 22301. A BCMS provides a holistic framework to help an organization prepare for, respond to, and recover from disruptive incidents. For a solar factory in Japan, this means looking beyond the facility’s walls.

Supply Chain Vulnerability

The 2011 earthquake also exposed the fragility of modern supply chains. The shutdown of a few key automotive parts manufacturers in the Tohoku region caused production halts at car factories around the world. A solar module factory is similarly dependent on a steady inflow of raw materials—solar cells, EVA, backsheets, glass—and a reliable outflow of finished products.

A robust continuity plan must address:

- Supplier Diversification: Identifying primary and secondary suppliers for critical components, preferably in different geographical regions.

- Inventory Strategy: Maintaining a strategic buffer of key raw materials to withstand short-term supply disruptions.

- Logistics Contingencies: Planning alternative transportation routes and logistics partners in case primary routes are compromised.

Integrating these considerations is a hallmark of professionally planned projects. For example, experience from J.v.G. Technology GmbH in deploying a turnkey solar panel production line shows that mapping supply chain risks early in the project is as important as the technical machine specifications.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Is it significantly more expensive to build a seismically resilient factory?

While there is a higher initial investment for advanced systems like base isolation, this must be weighed against the potential cost of downtime. A single week of lost production can easily exceed the marginal cost of enhanced seismic protection. The return on investment is measured in reduced risk and greater operational uptime.

Can an existing building be retrofitted for solar manufacturing in Japan?

Yes, retrofitting is possible, but it requires a thorough structural and seismic assessment by qualified local engineers. This process is often more complex and costly than a new build, as the existing structure may need significant reinforcement to meet both seismic standards and the specific load requirements of manufacturing equipment.

Does seismic resilience affect factory insurance premiums?

In many cases, yes. Demonstrating a comprehensive approach to seismic risk mitigation—including both structural and non-structural measures, as well as a formal business continuity plan—can lead to more favorable insurance terms and lower premiums.

What is the first step in planning a factory in a high-risk zone?

The first step is a comprehensive feasibility study and site assessment. This should be conducted with a partner experienced not only in solar manufacturing but also in industrial project planning within seismically active regions. It involves analyzing geological data, understanding local building codes, and integrating seismic design into the initial business plan.

Conclusion: Building a Lasting Enterprise in a Dynamic Environment

Establishing a solar module factory in Japan presents a unique set of challenges and opportunities. Success in this environment depends on a forward-thinking approach that prioritizes resilience over mere compliance.

By integrating advanced seismic engineering for the building and its equipment with a strategic business continuity plan for the wider operation, an investor can build an enterprise designed not just to survive, but to thrive for decades to come. While the technical complexities are significant, they need not be a barrier to entry. With expert guidance, entrepreneurs can navigate these challenges effectively, ensuring their investment is secure and their operations are built on a foundation of lasting stability.